Effective Use Of Rhetorical Questions In Jury Summation

By admin on February 26, 2014

The art of persuasion comes in many forms. Recently, we wrote an article about the plaintiff bar’s embrace of Reptile theory. The Reptile theory asserts that you can prevail at trial by speaking to, and scaring, the primitive part of jurors’ brains. However, good trial counsel can effectively utilize more traditional forms of persuasion in their summations. Trial counsel do not need to bring reptilian logic into the courtroom when they can rely on oratorical techniques that have effectively swayed audiences for centuries. Just consider Shakespeare’s use of rhetorical questions in Marc Anthony’s funeral oration in Julius Caesar, which turned mourners into an angry mob.

embrace of Reptile theory. The Reptile theory asserts that you can prevail at trial by speaking to, and scaring, the primitive part of jurors’ brains. However, good trial counsel can effectively utilize more traditional forms of persuasion in their summations. Trial counsel do not need to bring reptilian logic into the courtroom when they can rely on oratorical techniques that have effectively swayed audiences for centuries. Just consider Shakespeare’s use of rhetorical questions in Marc Anthony’s funeral oration in Julius Caesar, which turned mourners into an angry mob.

In an excellent article titled, “Case for the Rhetorical Question as a Summation Technique,” which appeared in the New York Law Journal on February 26, 2014, plaintiff lawyers Ben Rubinowitz and Evan Torgan demonstrate how the use of rhetorical questions can be effectively used during jury summation to reiterate and reinforce important parts of the plaintiff’s case. As the authors discuss, the use of rhetorical questions can be used with equal effectiveness by the defense, which of course is the raison d’être of this blog.

Rubinowitz and Torgan emphasize that trial counsel should always consider the language in the New York Pattern Jury Instructions before devising a rhetorical line of questions for use in summation. These instructions not only serve as a guide for the jury, but allows trial attorneys to create powerful arguments that fit neatly into those instructions.

In their article, the authors demonstrate the use of rhetorical questions: (1) when the defendant fails to call its expert examining physician to the witness stand; (2) when a party fails to call an important witness; or (3) in the case of spoliation of evidence.

For example, following is an illustation of their use of rhetorical questions during summation where key evidence has been lost or destroyed:

Ladies and gentlemen, there is one piece of evidence that is more important than any other piece of evidence in this case. You heard about that piece of evidence from the beginning of this case – from the opening statements forward. And you now know how important that piece of evidence is. You know that it would answer the most important question in this case. So ask yourselves, why wasn’t it produced? Why haven’t you been allowed to see that [piece of evidence]? Where is it? And why has it been kept from you? The answer is clear. It wasn’t produced for one reason and only one reason. If it was produced it would have made plaintiff’s claims meaningless. If it was produced it would have destroyed plaintiff’s arguments. And if it was produced it would have destroyed his case!

The hallmark of Rubinowitz/Torgan articles on trial practice is their effectiveness in providing the “buildup” or “setup” that practitioners can use in various phases of trial practice. Rubinowitz and Torgan teach us that it is not only springing the trap that matters, but the patient preparation that makes springing the trap all the more delicious! Shakespeare would be proud.

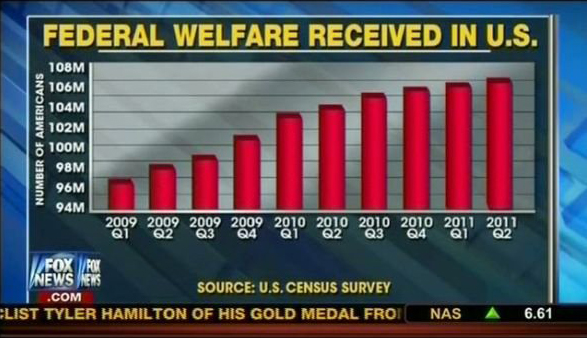

1. The Slippery Scale. This trick involves setting the the vertical y-axis on a graph in a narrow range that does not include “0.” By not including “0,” it is easy to make a relatively small change look enormous.

1. The Slippery Scale. This trick involves setting the the vertical y-axis on a graph in a narrow range that does not include “0.” By not including “0,” it is easy to make a relatively small change look enormous.

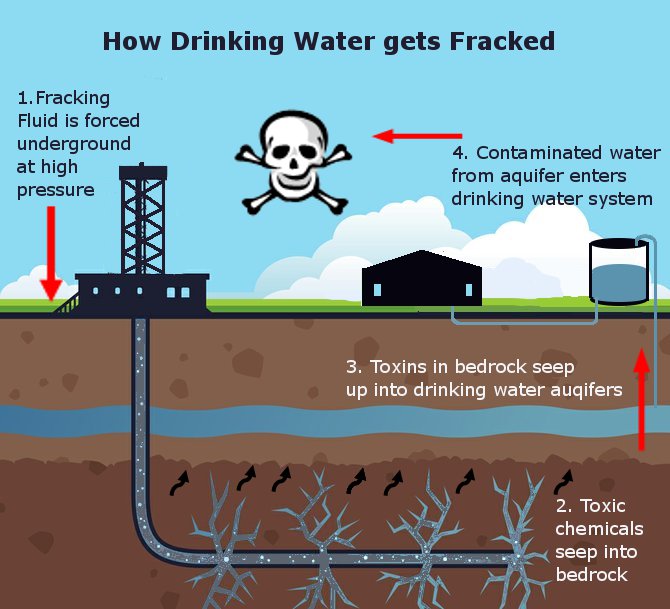

Perhaps the single most important Rule 403 objection you can make in a jury trial is the exhibit’s capacity to generate an emotional response such as pity, revulsion or contempt. Under these circumstances, the capacity to evoke emotion far outweighs the value of the evidence on the issues before the court and exclusion is appropriate.

Perhaps the single most important Rule 403 objection you can make in a jury trial is the exhibit’s capacity to generate an emotional response such as pity, revulsion or contempt. Under these circumstances, the capacity to evoke emotion far outweighs the value of the evidence on the issues before the court and exclusion is appropriate.