No Unanimity As To What New ASTM E1527-13 Standard Requires

By admin on October 11, 2013

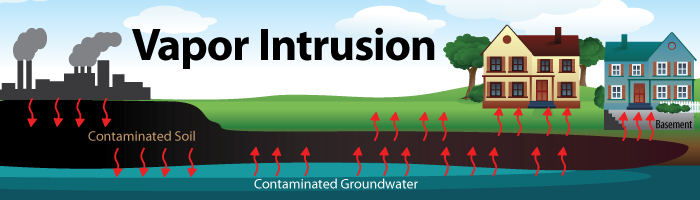

Some environmental practitioners contend that Phase I site assessments, commonly used in real estate transactions, will now be more costly and time consuming due to the new standard. Seyfarth Shaw counsels in its Client Alert that the new standard requires that, “if the subject property has soil contamination or is underlain by groundwater contamination, unless the risk of vapor intrusion can be screened out, Phase II sampling likely will be necessary.”

Some environmental practitioners contend that Phase I site assessments, commonly used in real estate transactions, will now be more costly and time consuming due to the new standard. Seyfarth Shaw counsels in its Client Alert that the new standard requires that, “if the subject property has soil contamination or is underlain by groundwater contamination, unless the risk of vapor intrusion can be screened out, Phase II sampling likely will be necessary.”

But is that really the case? In his article titled, “Confusion on Role of VI in New ASTM E1527-13 Standard,” environmental guru, Larry Schnapf, argues that these law firms’ predictions are “simply incorrect.” Schnapf points out that the revised version of E1527 clarifies that the vapor intrusion pathway is like any other contaminant’s pathway and the potential for vapor intrusion should be evaluated and addressed as part of a Phase I inspection.

However, all a consultant is required to do as part of a Phase I is to recognize environmental conditions – the presence or potential presence of releases of hazardous substances. A consultant that identifies a REC due to an actual or potential source of soil or groundwater contamination will not normally collect samples as part of a Phase I.

Contrary to the interpretation of the new Phase I standard offered by some, Schnapf advises:

From a practical standpoint, the question of whether vapor intrusion should be independently flagged as a REC will only really be an issue for off-site releases where vapor intrusion is the only pathway for contamination to migrate onto the property. When the target property already has soil or groundwater contamination, the consultant would flag that contamination as a REC.

Thus, according to Schnapf, if a consultant determines that there is potential vapor intrusion because of the presence of an REC, the consultant is not required to actually collect sub-slab or indoor air samples as part of its Phase I.

indoor air samples as part of its Phase I.

The issue takes on additional importance when one also considers that Phase I diligence is required to protect both landowners and lenders from liability under CERCLA.

According to USEPA,

"All Appropriate Inquiries," or AAI, is a process of evaluating a property’s environmental conditions and assessing the likelihood of any contamination…..The All Appropriate Inquiries Final Rule provides that the ASTM E1527-05 standard is consistent with the requirements of the final rule and may be used to comply with the provisions of the rule.

The Small Business Liability Relief and Brownfields Revitalization Act (the “Brownfields Amendments”) amended CERCLA to provide protections from liability for certain landowners and prospective purchasers of properties who can demonstrate compliance with specific statutory criteria and did not cause or contribute to contamination at the property.

Therefore, if the Phase I diligence the new owner performs does not meet the revised ASTM E1527-13 standard, in the opinion of the Agency, due to the omission of vapor intrusion screening, there may be considerable adverse consequences down the road for both landowners and lenders.

The additional transactional cost to the real estate community in performing many thousands of vapor intrusion studies in Phase I assessments each year is likely to be considerable. Considering that vapor intrusion is just one of many RECs, does it make sense from an environmental perspective to do these surveys as a matter of course? More importantly, does the new standard require that these screenings be performed at all?

What is the duty of a real estate developer to disclose to prospective residential purchasers information about the neighborhood that may adversely impact property values? Apparently none if the developer is not in privity with the homeowners, according to the Eleventh Circuit.

What is the duty of a real estate developer to disclose to prospective residential purchasers information about the neighborhood that may adversely impact property values? Apparently none if the developer is not in privity with the homeowners, according to the Eleventh Circuit. Until now, there has been a split of appellate authority in New York concerning what a prospective purchaser must show in seeking damages for a seller’s repudiation of a contract for the sale of real property. It is the general rule that a prospective purchaser seeking specific performance of a real estate contract must demonstrate that it is “ready, willing and able to close.” However, there has been a split of authority concerning whether the purchaser must demonstrate that it is “ready, willing and able” to close in seeking damages for seller’s anticipatory breach of contract.

Until now, there has been a split of appellate authority in New York concerning what a prospective purchaser must show in seeking damages for a seller’s repudiation of a contract for the sale of real property. It is the general rule that a prospective purchaser seeking specific performance of a real estate contract must demonstrate that it is “ready, willing and able to close.” However, there has been a split of authority concerning whether the purchaser must demonstrate that it is “ready, willing and able” to close in seeking damages for seller’s anticipatory breach of contract. In an

In an

Guest Blogger ANDREA J. LAWRENCE is a Senior Counsel at Epstein Becker & Green in New York. She provides legal advice and counsel to clients in the real estate industry. Andrea has extensive commercial litigation experience, and has provided legal representation to real estate companies, landlords, developers, property management companies, and commercial tenants She recently published an article about bed bug litigation in the

Guest Blogger ANDREA J. LAWRENCE is a Senior Counsel at Epstein Becker & Green in New York. She provides legal advice and counsel to clients in the real estate industry. Andrea has extensive commercial litigation experience, and has provided legal representation to real estate companies, landlords, developers, property management companies, and commercial tenants She recently published an article about bed bug litigation in the  A recent Michigan Court of Appeals decision,

A recent Michigan Court of Appeals decision,  although they could still be of concern to a property owner, tenant or lender. If you’re into fishing, this

although they could still be of concern to a property owner, tenant or lender. If you’re into fishing, this