Is Rule 30(b)(6) A Plaintiff’s Best Friend?

By admin on August 8, 2013

Rule 30(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides an efficient means of identifying the corporate representative with the most relevant knowledge concerning particular subjects at issue in a case. When a requesting party cannot identify the appropriate corporate witness to testify about particular activities or documents, Rule 30(b)(6) can be an invaluable tool.

Rule 30(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides an efficient means of identifying the corporate representative with the most relevant knowledge concerning particular subjects at issue in a case. When a requesting party cannot identify the appropriate corporate witness to testify about particular activities or documents, Rule 30(b)(6) can be an invaluable tool.

The corporate deposition may be fraught with risk, however, especially in a case involving skillful plaintiff counsel. This is particularly the case where testimony of the corporate representative may have importance in future or parallel litigation. Thus, If Rule 30(b)(6) is plaintiff’s counsel’s best friend, it is imperative that the corporate witness be properly prepared in the first instance. In a program titled, “Preparing the Corporate Witness,” which was presented to the attendees at the IADC’s 2013 Annual Meeting, Kay Barnes Baxter of Swetman Baxter Massenburg, LLC, Elizabeth Haecker Ryan of Coats Rose, and Terrence M.R. Zic of Whiteford Taylor Preston LLC provided an excellent overview of potential Rule 30(b)(6) pitfalls and how good preparation may help avoid them.

Upon receipt of the Rule 30(b)(6) notice, the first decision to make is whether to object to the notice. Is the notice overly broad and burdensome? Is the notice so vague that it is unclear precisely what information will be elicited at the deposition? Prior to discussing with the client what witness or witnesses to produce, it is imperative that both counsel and the client have a clear idea concerning the scope of the notice. The failure to timely object to the notice may come back to haunt the unwary defense counsel.

notice. Is the notice overly broad and burdensome? Is the notice so vague that it is unclear precisely what information will be elicited at the deposition? Prior to discussing with the client what witness or witnesses to produce, it is imperative that both counsel and the client have a clear idea concerning the scope of the notice. The failure to timely object to the notice may come back to haunt the unwary defense counsel.

The second decision to make is critical – who should be designated as the corporate representative? The rule does not require the person designated to be the individual “most knowledgeable” about the subject matter. However, there is nothing to prohibit the corporation from designating that person. Moreover, the rule does not require that the witness be an employee of the corporation. The rule indicates that a corporation may designate “other persons who consent to testify on its behalf.” On occasion, a former employee or a consultant may have the best information concerning the information at issue.

Perhaps the biggest challenge in preparing the corporate witness for deposition is that he or she must testify to “information known or reasonably available to the organization.” Thus, the corporate witness often is required to testify beyond his or her personal knowledge. The plaintiff generally wants to have it both ways. During the deposition, the plaintiff will seek to elicit hearsay testimony from the corporate witness. However, should the same corporate witness appear at trial, plaintiff’s counsel will most likely object to the admission of testimony unfavorable to the plaintiff on the ground that the witness does not have personal knowledge of the information.

Therefore, it is often a good strategy to consider conducting your own direct examination of the witness at the end of plaintiff’s examination so that you can make counter-designations of that testimony in the event that plaintiff’s counsel designates any portion of the witness’ testimony for trial. It is difficult for plaintiff to object to testimony on hearsay grounds if plaintiff has designated testimony from the same deposition for use at trial.

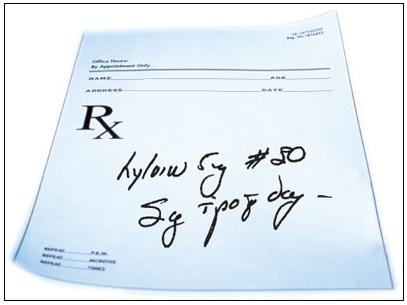

Every defense counsel has suffered through a deposition in which the client has seemingly forgotten everything that was painstakingly discussed during a prep session. Hopefully, if counsel has prepared the client well, her corporate witness will hopefully not give answers like:

"I don’t know what ABC Company thinks of what is written in this company document, although I know what I think it means." or

"This is me speaking, not the Company."

Of course, all answers are on behalf of the corporation and have the potential to be used against it , regardless of how the witness attempts to qualify an answer.

Of course, all answers are on behalf of the corporation and have the potential to be used against it , regardless of how the witness attempts to qualify an answer.

It is sometimes difficult to anticipate exactly what strategy plaintiff’s counsel will adopt in taking the deposition of a corporate witness. One good tip offered at the IADC program– If you know which plaintiff attorney will be taking the deposition, get a transcript from one of this attorney’s prior corporate depositions and go over with your witness the types of questions that will be asked and the phraseology that the attorney favors. Practice those questions and answers with the corporate witness. Your client should be prepared in the event she is asked what a witness might have been thinking when she wrote a particular document or if she is asked to provide a legal conclusion.

On February 11, 2013, the IADC conducted a lively, interactive panel discussing the risks and benefits of shale oil and gas extraction at the

On February 11, 2013, the IADC conducted a lively, interactive panel discussing the risks and benefits of shale oil and gas extraction at the

Courts have long struggled with hybrid fact scenarios that involve both a product and a service. When a corporate defendant is sued for personal injury, is it more advantageous for the defendant to be characterized as a service provider rather than a product manufacturer? The knee jerk reaction of some defense lawyers is that they would prefer their client to be cast as service providers. After all, who wants their client to be subjected to a strict liability product claim if it could be avoided, right? Not so fast. The answer to this question may be more complicated that it appears at first blush.

Courts have long struggled with hybrid fact scenarios that involve both a product and a service. When a corporate defendant is sued for personal injury, is it more advantageous for the defendant to be characterized as a service provider rather than a product manufacturer? The knee jerk reaction of some defense lawyers is that they would prefer their client to be cast as service providers. After all, who wants their client to be subjected to a strict liability product claim if it could be avoided, right? Not so fast. The answer to this question may be more complicated that it appears at first blush. In an article titled, “

In an article titled, “ The Texas Supreme Court rendered judgment in favor of

The Texas Supreme Court rendered judgment in favor of

We discussed in an

We discussed in an  .

.  In the majority of jurisdictions, to establish a claim for design defect in a product liability action, the plaintiff must present some proof of a “feasible alternative design” or “reasonable alternative design.”

In the majority of jurisdictions, to establish a claim for design defect in a product liability action, the plaintiff must present some proof of a “feasible alternative design” or “reasonable alternative design.”  In defending a United States defendant in an action involving a foreign accident and foreign claimants, it is almost a knee jerk reaction to file a motion to dismiss on

In defending a United States defendant in an action involving a foreign accident and foreign claimants, it is almost a knee jerk reaction to file a motion to dismiss on  A Lone Pine Order is a case management tool that requires toxic tort plaintiffs to produce credible evidence to support a key legal component of their claim prior to the commencement of pre-trial discovery. As

A Lone Pine Order is a case management tool that requires toxic tort plaintiffs to produce credible evidence to support a key legal component of their claim prior to the commencement of pre-trial discovery. As  In his recent article, "

In his recent article, "