New Fracking Rules Unveiled for Federal Lands

By Brian Roth, Chicago on March 30, 2015

On March 26, 2015, the Department of the Interior Bureau of Land Management (“BLM”) published its long-awaited final rule regarding hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) in the Federal Register, which becomes effective 90 days after publication, on June 24, 2015. The new rules mark the first update to federal fracking standards in more than 30 years. The new rules are effectively the first rules that squarely address horizontal hydraulic fracturing, as the technology did not exist in present form when the old rules were enacted.

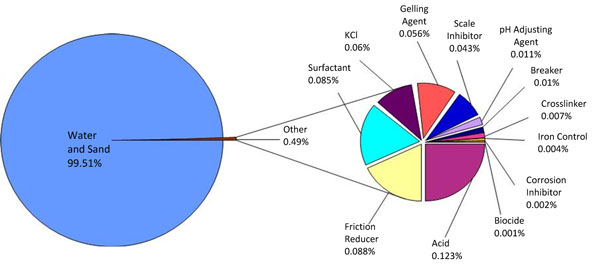

Fracking is an increasingly common, and politically polarizing, method for extracting fossil fuels. At bottom, fracking is a drilling technique used to recover gas and oil from shale rock. The process involves drilling into the earth and then injecting a high-pressured cocktail of water, sand, and chemicals down and eventually across horizontally drilled wells. The pressurized liquid fractures the subsurface rock, which consequently releases trapped oil and gas that is eventually pumped back to the surface.

Fracking is credited with advancing the recent U.S. “energy renaissance,” which has reduced oil prices to a two-decade low and allowed the U.S. to double its oil production from 2008 to 2015. In fact, the U.S. is now poised to become the world’s largest producer of oil and gas. Fracking is not without harsh and staunch critics, however, and the process has raised concerns among some regarding alleged contamination to groundwater, waste disposal, and the public’s exposure to toxic chemicals. Ardent opponents also point to air emissions and climate change, excessive water consumption, and even the increased risk of earthquakes. A recent Gallup poll suggests that Americans are equally divided on the use of fracking as a means of increasing natural gas and oil production in the U.S.

These concerns prompted several years of debate, culminating in the BLM’s final rules. The BLM intends

for the new rules to “serve[] as a much-needed complement to existing regulations designed to ensure the environmentally responsible development of oil and gas resources on Federal and Indian lands, which were finalized nearly thirty years ago, in light of the increasing use and complexity of hydraulic fracturing coupled with advanced horizontal drilling technology.” The BLM’s final rules are the first set in what is expected to be a series of federal rules governing fracking.

In sum, the new standards impose numerous new requirements on companies. The hallmarks include:

- Companies must publicly disclose additive chemicals used in the fracking process on FracFocus, which is an industry-run website, within 30 days of completing fracking operations. This requirement, however, has already been adopted by many states that have examined the issue.

- Companies must allow government employees to inspect and validate (1) the safety of the concrete barriers lining fracking wells, and (2) chemicals being stored at the fracking site.

- Companies must adhere to new requirements and specifications or how to safely dispose of contaminated water.

- Companies must submit detailed information about every proposed operation, including the location of faults and fractures, the depths of usable water, and the depth of estimated volume of fluid to be used.

- Companies must submit detailed information about the geology, depth, and locations of already exiting wells.

Despite what many perceive as laudable objectives, the fear among oil and gas companies is that the BLM’s new rules will drastically increase production costs (thereby adversely affecting oil prices), as well as stifle energy development. Indeed, the American Petroleum Institute (“API”), relying on research and consulting firm Advanced Resources International, analyzed a draft of the final rule and “estimate[d] that the total costs associated with this rule could range from $30 million per year to $2.7 billion per year.” The API suggests that the requirement of “cement evaluation logs” (“CELs”) on surface and intermediate casing before beginning the fracking process as a source of added cost. The Western Energy Alliance (“WEA”)—whose members include ConocoPhillips, Halcon Resources Corp. and QEP Resources Inc.—relying on an economic research firm’s analysis, provided a more focused prediction that the added cost of compliance would be $97,000 per new well, or $345.592 million annually. The WEA warns that considerable costs will emanate from initial delay costs, administrative costs, enhanced casing costs, cement log costs for “well types,” and cement log delay costs. Although energy trade associations are still assessing the precise costs of the new rules, many expect that the associated costs will greatly exceed the BLM’s rather conservative estimate of $11,400 per well, or $32 million annually.

The new rules have already prompted several lawsuits challenging their legality, characterizing them as “arbitrary and unnecessary burdens” that are “a reaction to unsubstantiated concerns.” One lawsuit was filed by the Independent Petroleum Association of American and the Western Energy Alliance. Another was filed by the State of Wyoming. These parties are significant stakeholders that have a sizeable presence on federal lands, and consequently they have a lot to lose with the increased cost of compliance with the new rules. Even for those entities intent on compliance, the new rules are lengthy and complicated, and will require legal consultation with attorneys specializing in the area.

As a final and important note, the rules apply to fracking on federal lands, which accounts for only approximately 10 percent of all fracking nationwide and 5 percent of all domestic oil production. The states have jurisdiction over fracking on state-owned and private land, and thus the BLM’s new rules do not apply. Accordingly, these rules do not affect the vast majority of U.S. fracking operations. Nonetheless, the BLM hopes that its new rules will eventually serve as a model and legislative benchmark for states seeking to regulate the fracking industry within their borders.

After studying one particular site in western Pennsylvania for 18 months, the DOE determined that neither fracking chemicals nor brine water from the gas drilling process had contaminated area drinking water. The report said that the chemicals used in fracking remained approximately 5,000 feet below drinking water supplies. The study marked the first occasion where a company agreed to have its fracking operations independently monitored.

After studying one particular site in western Pennsylvania for 18 months, the DOE determined that neither fracking chemicals nor brine water from the gas drilling process had contaminated area drinking water. The report said that the chemicals used in fracking remained approximately 5,000 feet below drinking water supplies. The study marked the first occasion where a company agreed to have its fracking operations independently monitored. It is necessary that natural gas be substituted for coal and oil as an energy source if the world is to have any chance of avoiding runaway greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions, particularly from the developing world.

It is necessary that natural gas be substituted for coal and oil as an energy source if the world is to have any chance of avoiding runaway greenhouse gas (“GHG”) emissions, particularly from the developing world. effective regulation and by self-policing by industry. From the standpoint of providing an inexpensive fuel to tens of millions of American homeowners, the stakes are simply too high for environmentalists, who support fracking with these reservations, to concede defeat. As industry continues to demonstrate that fracking can be performed in a safe and environmentally sound manner, opposition to the practice will most likely diminish.

effective regulation and by self-policing by industry. From the standpoint of providing an inexpensive fuel to tens of millions of American homeowners, the stakes are simply too high for environmentalists, who support fracking with these reservations, to concede defeat. As industry continues to demonstrate that fracking can be performed in a safe and environmentally sound manner, opposition to the practice will most likely diminish. The NYLCV’s

The NYLCV’s  fighting for our future until we are start drilling here in New York state”. In an

fighting for our future until we are start drilling here in New York state”. In an  Local bans on hydraulic fracturing continue to be fiercely debated as the use of hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas development of shale reserves increasingly gains in popularity. Grassroots opponents of hydraulic fracturing increasingly stress the non-environmental social impacts that have become associated with hydraulic fracturing in certain rural communities.

Local bans on hydraulic fracturing continue to be fiercely debated as the use of hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas development of shale reserves increasingly gains in popularity. Grassroots opponents of hydraulic fracturing increasingly stress the non-environmental social impacts that have become associated with hydraulic fracturing in certain rural communities.  their communities.

their communities. Pennsylvanians now await a decision from the Supreme Court, in the wake of a Commonwealth Court decision, which found that that Act 13 cannot restrict zoning. The state had argued in that case that zoning provisions in Act 13 do not pre-empt local governments from enacting zoning ordinances so long as they did not place any restrictions on the location of oil and gas drilling operations in conflict with Act 13.

Pennsylvanians now await a decision from the Supreme Court, in the wake of a Commonwealth Court decision, which found that that Act 13 cannot restrict zoning. The state had argued in that case that zoning provisions in Act 13 do not pre-empt local governments from enacting zoning ordinances so long as they did not place any restrictions on the location of oil and gas drilling operations in conflict with Act 13.

the Interstate Environmental Commission, a tri-state water and air quality enforcement authority, where she conducted and managed litigation to control and abate water pollution and ensure adequate water and sewer infrastructure. She teaches environmental law at the Syracuse University College of Law.

the Interstate Environmental Commission, a tri-state water and air quality enforcement authority, where she conducted and managed litigation to control and abate water pollution and ensure adequate water and sewer infrastructure. She teaches environmental law at the Syracuse University College of Law.