How Much is too Much? Counsel’s Active Conduct in Asbestos Suit Results in Forfeiture of Jurisdictional Defense

By Andrew Bullard, Hartford and Cullen Guilmartin, Hartford on June 9, 2016

Since the  U.S. Supreme Court handed down Daimler AG v. Bauman 134 S.Ct. 746 (2014), personal jurisdiction defenses have experienced a renaissance in asbestos litigation. Defendants that wish to win such arguments, however, are well advised to heed a recent ruling by Judge Gibney, who presides over Rhode Island’s state court asbestos docket. In Bazor v. Abex Corporation et al., C.A. No. PC-10-3965 (R.I. Super. May 2, 2016), Judge Gibney issued a ruling that is instructive on what a defendant must do to preserve its right to contest jurisdiction, holding that a defense counsel’s “active conduct constitute[d] forfeiture of the defense of lack of personal jurisdiction.” The court referred to “forfeiture” as opposed to “waiver” because the defendant had properly asserted the lack of personal jurisdiction as a special defense.

U.S. Supreme Court handed down Daimler AG v. Bauman 134 S.Ct. 746 (2014), personal jurisdiction defenses have experienced a renaissance in asbestos litigation. Defendants that wish to win such arguments, however, are well advised to heed a recent ruling by Judge Gibney, who presides over Rhode Island’s state court asbestos docket. In Bazor v. Abex Corporation et al., C.A. No. PC-10-3965 (R.I. Super. May 2, 2016), Judge Gibney issued a ruling that is instructive on what a defendant must do to preserve its right to contest jurisdiction, holding that a defense counsel’s “active conduct constitute[d] forfeiture of the defense of lack of personal jurisdiction.” The court referred to “forfeiture” as opposed to “waiver” because the defendant had properly asserted the lack of personal jurisdiction as a special defense.

In this instance, the “active participation” included the following conduct during the two years and nine months between the filing of an answer and the motion to dismiss: filing an objection to the trial date, attending a plaintiff’s deposition, requesting and participating in the reopening of that deposition, participating in the deposition of the plaintiffs’ expert, objecting to the expert’s deposition on non-jurisdictional grounds, disclosing eight expert witnesses, filing 15 motions in limine, supplementing its expert witness disclosure, producing two expert witnesses for depositions, responding to discovery (without preserving the defense of lack of personal jurisdiction), supplementing its expert discovery, moving to compel the production of the plaintiffs’ bankruptcy trust documents, and participating in at least ten status/settlement conferences. In short, defense counsel’s very active participation in the litigation was so active so as to constitute “forfeiture” of a claim of lack of personal jurisdiction.

Looking to federal jurisprudence for guidance, the court focused on defense counsel’s litany of activity over several years. Synthesizing federal decisions, the court identified two principal elements to weigh to determine whether a defense of personal jurisdiction is forfeited: (a) the delay in asserting the defense; and (b) the “nature and extent” of the defendant’s involvement in the case. The court noted that the first factor could be met by as little as four months’ delay; but reasoned that the second factor weighed more heavily than the mere passage of time. With regard to the second factor, the court cited defendant’s filing of an appearance, participation in discovery, attending and taking depositions, and filing and opposing motions as evidence of active participation. Notably, the court found that the defendant had created “substantial delay” without “a sufficiently meritorious reason” for failing to assert its defense for two years and nine months after the filing of its answer. The level of participation appears to have been the deciding factor; with special attention brought to “the fifteen motions in limine [defendant] filed which sought merits-based rulings” and the failure to continually assert the defense throughout the course of litigation. However, of concern is that the ruling did nothing to establish a “bright line” rule of precisely how much participation is “too much” so as to result in a forfeiture of a jurisdictional defense.

It is unclear where this decision leaves litigants who need to participate in early discovery and who also want to preserve their jurisdictional defenses. Defendants who wish to maintain their defenses are faced with choosing from various interpretations of the Bazor decision, focusing on the assertion of their rights and carefully monitoring the level of their participation. The decision could reasonably be read to indicate that a party may participate in discovery, but only if they continue to maintain and pursue their jurisdictional defense. Alternatively, some parties may refuse to participate in non-jurisdictional discovery for fear of inadvertent forfeiture. This may create friction with plaintiff’s counsel when their clients are in poor health, which frequently occurs in asbestos cases across the country. Ultimately, the lesson of Bazor may be that safest resolution for defense counsel will be to file and pursue dispositive jurisdictional motions as early in the case as possible. At the very least, defense counsel should raise the defense in pleadings and discovery which precede the filing of the motion to dismiss on jurisdictional grounds and/or reach some sort of agreement with opposing counsel to prevent forfeiture despite some level of active participation in the case. For example, defense counsel in the asbestos litigation should obtain a stipulation that attendance at an exigent deposition does not constitute a waiver of personal jurisdiction arguments; and that stipulation should be placed on the record.

Rule 30(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides an efficient means of identifying the corporate representative with the most relevant knowledge concerning particular subjects at issue in a case. When a requesting party cannot identify the appropriate corporate witness to testify about particular activities or documents, Rule 30(b)(6) can be an invaluable tool.

Rule 30(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides an efficient means of identifying the corporate representative with the most relevant knowledge concerning particular subjects at issue in a case. When a requesting party cannot identify the appropriate corporate witness to testify about particular activities or documents, Rule 30(b)(6) can be an invaluable tool. notice. Is the notice overly broad and burdensome? Is the notice so vague that it is unclear precisely what information will be elicited at the deposition? Prior to discussing with the client what witness or witnesses to produce, it is imperative that both counsel and the client have a clear idea concerning the scope of the notice. The failure to timely object to the notice may come back to haunt the unwary defense counsel.

notice. Is the notice overly broad and burdensome? Is the notice so vague that it is unclear precisely what information will be elicited at the deposition? Prior to discussing with the client what witness or witnesses to produce, it is imperative that both counsel and the client have a clear idea concerning the scope of the notice. The failure to timely object to the notice may come back to haunt the unwary defense counsel. Of course, all answers are on behalf of the corporation and have the potential to be used against it , regardless of how the witness attempts to qualify an answer.

Of course, all answers are on behalf of the corporation and have the potential to be used against it , regardless of how the witness attempts to qualify an answer.  Federal court practitioners are well-advised to be aware of the key provisions of the

Federal court practitioners are well-advised to be aware of the key provisions of the

amount in controversy by a “preponderance of the evidence.” Under the new rule, if challenged, a defendant is required to present more than a conclusory statement that the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000.

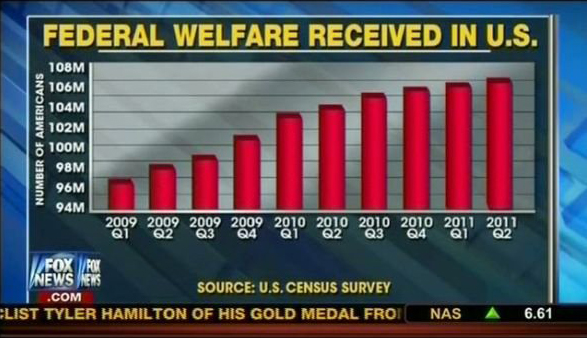

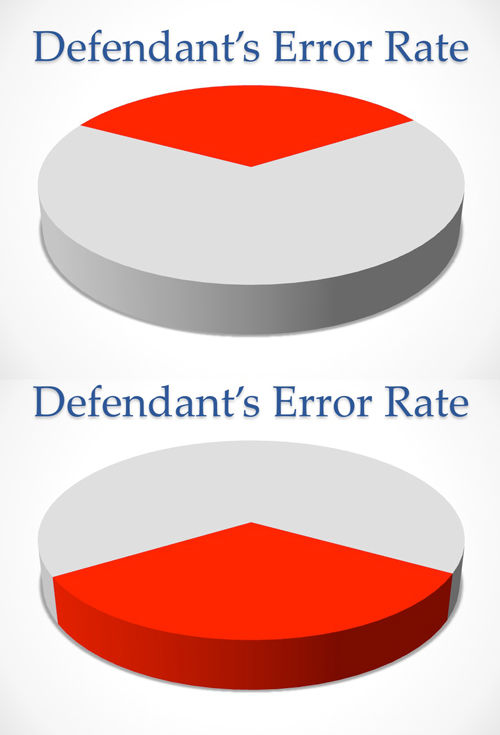

amount in controversy by a “preponderance of the evidence.” Under the new rule, if challenged, a defendant is required to present more than a conclusory statement that the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000. 1. The Slippery Scale. This trick involves setting the the vertical y-axis on a graph in a narrow range that does not include “0.” By not including “0,” it is easy to make a relatively small change look enormous.

1. The Slippery Scale. This trick involves setting the the vertical y-axis on a graph in a narrow range that does not include “0.” By not including “0,” it is easy to make a relatively small change look enormous.

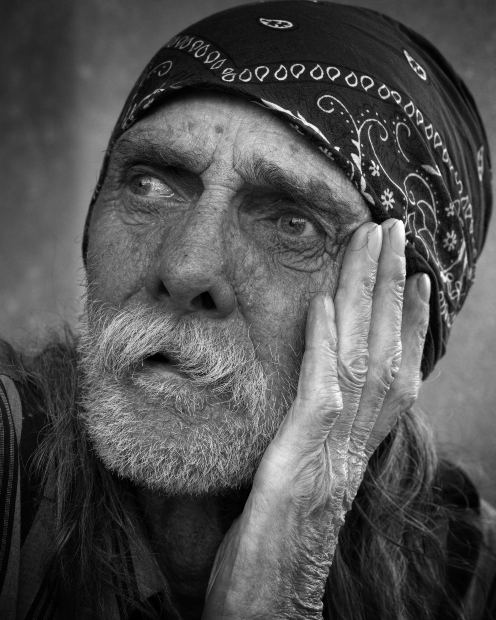

Perhaps the single most important Rule 403 objection you can make in a jury trial is the exhibit’s capacity to generate an emotional response such as pity, revulsion or contempt. Under these circumstances, the capacity to evoke emotion far outweighs the value of the evidence on the issues before the court and exclusion is appropriate.

Perhaps the single most important Rule 403 objection you can make in a jury trial is the exhibit’s capacity to generate an emotional response such as pity, revulsion or contempt. Under these circumstances, the capacity to evoke emotion far outweighs the value of the evidence on the issues before the court and exclusion is appropriate. The Toxic Tort Litigation Blog brings to the attention of defense practitioners weapons to add to their defense arsenal. An article in the Bloomberg BNA Toxics Law Reporter (6/14/02), titled "

The Toxic Tort Litigation Blog brings to the attention of defense practitioners weapons to add to their defense arsenal. An article in the Bloomberg BNA Toxics Law Reporter (6/14/02), titled " How successful have Twiqbal motions been in product liability cases? A

How successful have Twiqbal motions been in product liability cases? A  We discussed in an

We discussed in an  .

.  For the toxic tort practitioner, the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence is an indispensable reference work. As with previous editions, the Third Edition is organized according to the important scientific and technological disciplines often encountered by federal (or state) judges. It would be difficult to imagine preparing any toxic tort case for trial (or the filing of a Daubert motion) without reviewing, for example, the manual’s chapters on exposure science, epidemiology, toxicology, neuroscience and/or engineering.

For the toxic tort practitioner, the Reference Manual on Scientific Evidence is an indispensable reference work. As with previous editions, the Third Edition is organized according to the important scientific and technological disciplines often encountered by federal (or state) judges. It would be difficult to imagine preparing any toxic tort case for trial (or the filing of a Daubert motion) without reviewing, for example, the manual’s chapters on exposure science, epidemiology, toxicology, neuroscience and/or engineering.  In defending a United States defendant in an action involving a foreign accident and foreign claimants, it is almost a knee jerk reaction to file a motion to dismiss on

In defending a United States defendant in an action involving a foreign accident and foreign claimants, it is almost a knee jerk reaction to file a motion to dismiss on  In a recent decision, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals provided insurance companies doing business in Indiana with guidance on how to draft pollution exclusion clauses—provisions typically included in commercial general liability (“CGL”) policies that seek to exclude coverage for claims based on environmental contamination. Indiana is known for the tough standards it imposes on insurance companies with respect to withholding coverage based on policy exclusions. Since the Indiana Supreme Court’s 1996 decision in

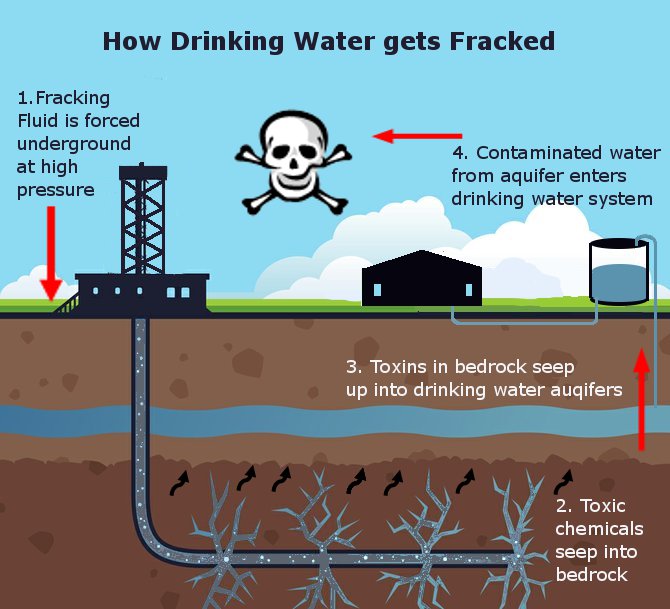

In a recent decision, the Seventh Circuit Court of Appeals provided insurance companies doing business in Indiana with guidance on how to draft pollution exclusion clauses—provisions typically included in commercial general liability (“CGL”) policies that seek to exclude coverage for claims based on environmental contamination. Indiana is known for the tough standards it imposes on insurance companies with respect to withholding coverage based on policy exclusions. Since the Indiana Supreme Court’s 1996 decision in  and associated piping from a 7-Eleven gas station in Goshen, Indiana. The petroleum contaminated the groundwater and migrated underneath a nearby residential neighborhood. The contamination vaporized into homes causing property damage and personal injury. The neighborhood residents sued 7-Eleven and West Bend Mutual Insurance Company’s (“West Bend”) and Federated’s mutual insured, MDK, who formerly owned and operated the station. After lengthy litigation, MDK eventually settled for $4 million. West Bend sued Federated to recover its costs of defending MDK.

and associated piping from a 7-Eleven gas station in Goshen, Indiana. The petroleum contaminated the groundwater and migrated underneath a nearby residential neighborhood. The contamination vaporized into homes causing property damage and personal injury. The neighborhood residents sued 7-Eleven and West Bend Mutual Insurance Company’s (“West Bend”) and Federated’s mutual insured, MDK, who formerly owned and operated the station. After lengthy litigation, MDK eventually settled for $4 million. West Bend sued Federated to recover its costs of defending MDK.