California’s Proposition 65 Runs Amok with Addition of BPA

By Brian Ledger, Los Angeles on April 4, 2016

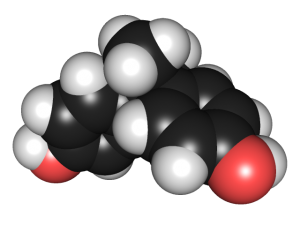

On May 11, 2015, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) listed Bisphenol A (BPA) as a reproductive toxicant to be added to the list of chemicals subject to Proposition 65. Given the widespread use of BPA in numerous consumer applications (e.g., plastics, adhesives, sealants, epoxy resin liners in food containers, and thermal paper such as the paper used to print cash register receipts), the addition of BPA is a significant development for a large number of businesses evaluating compliance with Proposition 65 with respect to BPA in products.

On May 11, 2015, the California Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA) listed Bisphenol A (BPA) as a reproductive toxicant to be added to the list of chemicals subject to Proposition 65. Given the widespread use of BPA in numerous consumer applications (e.g., plastics, adhesives, sealants, epoxy resin liners in food containers, and thermal paper such as the paper used to print cash register receipts), the addition of BPA is a significant development for a large number of businesses evaluating compliance with Proposition 65 with respect to BPA in products.

Proposition 65 provides a 12-month period from the date of listing before warnings are required. Thus, warnings for exposures to BPA will be required starting on May 11, 2016, unless a person in the course of doing business can show that exposures are below the Maximum Allowable Dose Level (MADL) safe harbor limit for BPA.

OEHHA Takes Action with Deadline Approaching

As the deadline for the warning requirement is quickly approaching, OEHHA recently took emergency action with respect to the listing of BPA. The first action was the issuance of a notice of proposed rulemaking to establish a MADL for dermal exposures from solid materials containing BPA. The second was an emergency action to allow for the temporary use of a standard point-of-sale warning for BPA exposures from canned and bottled foods and beverages.

Proposed MADL

The warning requirements under Proposition 65 do not apply if a business can show that exposures from a product are less than the MADL established by OEHHA, which puts the business in a “safe harbor.” Based on OEHHA’s review of the scientific studies, it has proposed a MADL of 3 micrograms/day (dermal exposure from solid materials) for BPA. Significantly, the proposed MADL of 3 micrograms/day is a level believed to be above that which most people would encounter from a product in normal use.

Comments on the proposed MADL are due to OEHHA by May 16, 2016. Note that this means that the proposed MADL will not be finalized until after the May 11, 2016 trigger date for warnings.

OEHHA Allows Uniform Point-of-Sale Warnings for Canned and Bottled Food and Beverages

OEHHA attempted to develop a MADL for oral exposure (as opposed to the dermal exposures discussed above) that could have precluded the need for an emergency action on the warnings. However, OEHHA was unable to work through the technical, practical, and timing issues associated with adopting an oral exposure MADL. Consequently, to avoid potential removal of many food products from the shelves in markets, OEHHA’s proposed solution, as presented in the emergency action, is to amend the regulations to provide for the temporary use of a standard point-of-sale warning as a compliance option.

The compliance option contemplates signs no smaller than 5 x 5 inches with the following warning language:

WARNING: Many cans containing foods and beverages sold here have epoxy linings used to avoid microbial contamination and extend shelf life. Lids on jars and caps on bottles may also have epoxy linings. Some of these linings can leach small amounts of bisphenol A (BPA) into the food or beverage. BPA is a chemical known to the State of California to cause harm to the female reproductive system. For more information go to: www.P65Warnings.ca.gov/BPA.

OEHHA’s actions will have a significant impact on businesses seeking to comply with Proposition 65 for products carrying the potential for exposures to BPA.

a chemical exposure toxic tort case in which plaintiff presents a case for toxic chemical exposure with a twist. Plaintiff’s decedent worked for some thirty years at the defendant’s facility as a maintenance worker. During the last five years of his life, he was allegedly exposed to a variety of chemical products, including industrial cleaners. One of these cleaners was involved in the chrome plating process. John’s issue is this. None of the Industrial Hygiene reports issued for the 5 years prior to his death show any exposure levels above the

a chemical exposure toxic tort case in which plaintiff presents a case for toxic chemical exposure with a twist. Plaintiff’s decedent worked for some thirty years at the defendant’s facility as a maintenance worker. During the last five years of his life, he was allegedly exposed to a variety of chemical products, including industrial cleaners. One of these cleaners was involved in the chrome plating process. John’s issue is this. None of the Industrial Hygiene reports issued for the 5 years prior to his death show any exposure levels above the