Illinois Appellate Court Reverses $4.6M Verdict: No Duty If No Knowledge of Product Risks, and Presence on Site Not Enough for Causation

By Mary McKenna, Chicago on September 11, 2018

On Sept. 5, 2018, an Illinois appellate court reversed a McLean County $4.6 million jury verdict against defendant Hobart Brothers Company on two grounds that offer hope to defendants in other cases. First, the court ruled that the defendant owed no duty to warn if defendant and the industry were unaware of a hazard in their asbestos-containing product at the time of plaintiff’s exposure, even if they were aware of the dangers of raw asbestos. Second, the court ruled that the mere presence of a defendant’s product at plaintiff’s workplace is insufficient evidence that the defendant’s product was a substantial cause of plaintiff’s mesothelioma.

On Sept. 5, 2018, an Illinois appellate court reversed a McLean County $4.6 million jury verdict against defendant Hobart Brothers Company on two grounds that offer hope to defendants in other cases. First, the court ruled that the defendant owed no duty to warn if defendant and the industry were unaware of a hazard in their asbestos-containing product at the time of plaintiff’s exposure, even if they were aware of the dangers of raw asbestos. Second, the court ruled that the mere presence of a defendant’s product at plaintiff’s workplace is insufficient evidence that the defendant’s product was a substantial cause of plaintiff’s mesothelioma.

BACKGROUND

Plaintiff brought suit against defendant for failure to warn of the dangerousness of its product—Hobart 6010 welding stick electrodes, which contained chrysotile asbestos in the flux. Plaintiff himself did not use the Hobart 6010 welding rods. Rather, he testified that for seven months in 1962 and 1963, stick welders using those rods worked on a grated mezzanine above his work area, and that the used stubs of the stick welders’ 6010 welding rods would fall through the grated mezzanine floor, onto the floor below where plaintiff performed spot-welding. Plaintiff also testified that each day, he had to walk by the stick welders and over the mezzanine floor which was littered with welding stubs.

LACK OF DUTY

The appellate court stated that whether the defendant had a duty, in 1962 and 1963, to warn about its welding rods depended on whether, in 1962 or 1963, knowledge existed in the industry of the dangerous propensity of the defendant’s welding rods.

Although there was evidence that, in 1962 and 1963, knowledge existed in the industry of the dangerous propensity of raw asbestos, the court made “a crucial distinction” between raw asbestos and welding rods containing encapsulated asbestos. Knowledge about raw asbestos was not evidence that knowledge existed in the industry that this product—the Hobart 6010 welding rod—was harmful. The appellate court ultimately found that the record contained no evidence of contemporaneous knowledge in the industry that welding rods with asbestos encapsulated in the flux were hazardous. The lack of knowledge resulted in a lack of duty, entitling defendant to judgment notwithstanding the verdict.

LACK OF SUBSTANTIVE CAUSATION EVIDENCE

The appellate court found that the defendant was likewise entitled to a judgment notwithstanding the verdict because the record was devoid of any evidence that defendant’s welding rods were a substantial cause of plaintiff’s mesothelioma.

The court ruled that the chestnut Illinois case of Thacker v. UNR Industries, Inc., 151 Ill. 2d 343 (1992) did not help plaintiff. Thacker involved raw asbestos, not a finished asbestos-containing product like the welding rods here. More significantly: “Proving merely that plaintiff came into frequent, close, and regular contact with welding rods manufactured by defendant would not, on the logic of Thacker, prove substantial causation any more than proving he routinely walked on floor tiles containing asbestos would prove substantial causation.” [¶77] Rather, to meet his burden of production, the plaintiff “must prove he actually inhaled respirable fibers from defendant’s welding rods—and that he inhaled enough of the fibers that one could meaningfully say the welding rods were a ‘substantial factor’ in causing his mesothelioma.” [¶78]

The appellate court ruled that the Thacker frequency, proximity and regularity criteria had not been met. For instance, although plaintiff worked on the second floor and the stick welders worked on the third floor, his work station was not directly below the grated mezzanine floor where the stick welders worked, but rather off to the side. Further, the appellate court noted that plaintiff testified that the stubs from the stick welders on the third floor fell through the grates of the mezzanine floor and onto the second floor, but that plaintiff did not testify that the stubs fell into his work area. Although plaintiff testified that his workplace was dirty, there was no evidence that the dirt indeed contained asbestos. Moreover, plaintiff never testified to seeing clouds of dust in the workplace (unlike in Thacker where various employees testified that dust from the sacks of raw asbestos was continuously visible in the air of the plant when viewed in bright light).

“For all that appears in the record, the amount of asbestos fibers released from defendant’s welding rods by rubbing them together or stepping on them was no more than the amount one would have encountered in a natural environment. Without any idea of the concentration of airborne asbestos fibers the welding rods would have produced, it would be conjectural to say the welding rods were a substantial factor in causing plaintiff’s mesothelioma.” [¶ 83]

TAKE AWAYS

Though this case involved the specific product of asbestos-containing welding rods, the potential effect on future failure-to-warn cases involving other asbestos-containing products is much broader. Importantly, the appellate court focused on the industry’s knowledge of the dangerous propensity of the manufacturer’s product itself, not on the industry’s knowledge of the dangerous propensity of asbestos generally. In so doing, the appellate court distinguished the inquiry as a product-specific issue, not as a more general asbestos issue. Going forward, each failure-to-warn case will need to be carefully considered based on its individual facts regarding the product, time frame and industry knowledge of the hazards of the product at issue at the time of exposure to determine whether a duty existed.

Furthermore, this decision may likely impact the scrutiny of causation evidence. In its application of Thacker, the appellate court discussed the need for a plaintiff to prove more than just frequent, close and regular contact with a defendant’s product; a plaintiff must also prove that he not only inhaled respirable fibers from the defendant’s product but also inhaled enough of the fibers that one could meaningfully say the defendant’s product was a substantial factor in causing a plaintiff’s disease. Additionally, the appellate court’s decision peripherally touched on alternative exposures. The extent of this decision’s impact in asbestos-related lawsuits remains to be seen. Nevertheless, it is a favorable ruling for defendants in asbestos litigation.

Read the full opinion in McKinney v. Hobart Brothers Company here.

The typical “take-home” plaintiff is a bystander such as the child who claims she was exposed to asbestos while playing in the basement where her father’s work clothes covered with asbestos dust were laundered. Across the United States, the battle lines are being drawn in these “take-home” or “household” asbestos cases. In a

The typical “take-home” plaintiff is a bystander such as the child who claims she was exposed to asbestos while playing in the basement where her father’s work clothes covered with asbestos dust were laundered. Across the United States, the battle lines are being drawn in these “take-home” or “household” asbestos cases. In a  "limitless liability", New York trial courts continue to distinguish cases on their facts to permit recovery for "take-home" claimants.

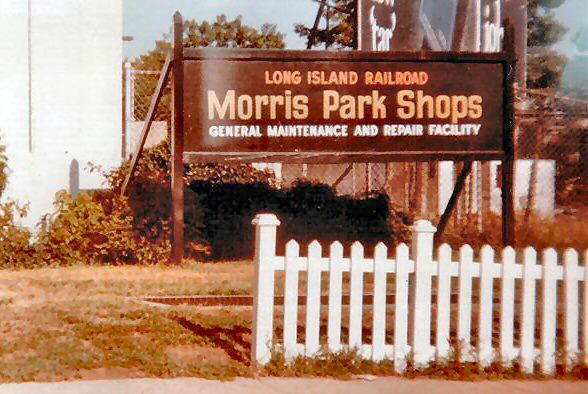

"limitless liability", New York trial courts continue to distinguish cases on their facts to permit recovery for "take-home" claimants.  Judge Heitler ruled that the Court of Appeals holding in Holdampf could not be relied upon by the LIRR because the facts presented in Frieder were different, to wit, LIRR had control of the workplace where the dinner was located (inside the walls of the rail yard). Under this unique set of facts, she reasoned, her ruling would neither run afoul of Holdampf nor open the floodgates of "limitless liability". Based upon her discussion of the "take-home" case law, Judge Heitler appears prepared to apply the brakes to "take-home" asbestos claims in New York City.

Judge Heitler ruled that the Court of Appeals holding in Holdampf could not be relied upon by the LIRR because the facts presented in Frieder were different, to wit, LIRR had control of the workplace where the dinner was located (inside the walls of the rail yard). Under this unique set of facts, she reasoned, her ruling would neither run afoul of Holdampf nor open the floodgates of "limitless liability". Based upon her discussion of the "take-home" case law, Judge Heitler appears prepared to apply the brakes to "take-home" asbestos claims in New York City.  On March 27, 2013, a jury in federal district court in Bridgeport, Connecticut awarded Cara Munn, a 20-year-old woman who formerly attended the

On March 27, 2013, a jury in federal district court in Bridgeport, Connecticut awarded Cara Munn, a 20-year-old woman who formerly attended the

Two strong CT trial lawyers squared off against each for this eight day trial–for the plaintiffs,

Two strong CT trial lawyers squared off against each for this eight day trial–for the plaintiffs,