Student Bitten By Tick: Hotchkiss School On Hook For $41.75 Million

By admin on April 5, 2013

On March 27, 2013, a jury in federal district court in Bridgeport, Connecticut awarded Cara Munn, a 20-year-old woman who formerly attended the Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, Connecticut, $41,750,000 in a case styled Orson D. Munn III et al. v. The Hotchkiss School, No. 3:09cv0919 (SRU). The case raises important issues concerning “duty” and “assumption of risk”.

On March 27, 2013, a jury in federal district court in Bridgeport, Connecticut awarded Cara Munn, a 20-year-old woman who formerly attended the Hotchkiss School in Lakeville, Connecticut, $41,750,000 in a case styled Orson D. Munn III et al. v. The Hotchkiss School, No. 3:09cv0919 (SRU). The case raises important issues concerning “duty” and “assumption of risk”.

The jury determined that Hotchkiss, a prestigious prep school, was negligent for two reasons: (1) in failing to warn plaintiff before or during a school sponsored trip to China during the summer of 2007 about the risk of insect-borne illness on the trip; and (2) in failing to ensure that plaintiff used protective measures to prevent infection by an insect-borne disease while visiting Mt. Pan in China.

In an article appearing in the Connecticut Law Tribune (Vol. 39, No. 13), titled “Tick Bite Leads To Big Verdict“, it was reported that the school was faulted specifically for not warning plaintiff (and her parents) that she would be traveling in mountainous and forested terrain. As a result, the jury determined that the plaintiff was not aware that she had to protect herself from insects by wearing bug repellent, long sleeve shirts and trousers, and by avoiding brushy undergrowth.

According to Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint, Ms. Munn’s parents had Cara flown back to the United States in July ’07, where she was hospitalized for several weeks at Weill Cornell Medical Center in the pediatric ICU and later at the Rusk Institute for extensive rehab. As a result of her severe encephalitis, plaintiff suffered severe neurological and motor injuries, including permanent loss of speech.

The case, which will almost certainly be appealed, raises significant issues concerning duty and the assumption of personal responsibility by parents who agree to have their child travel abroad for educational purposes. Apart from the obvious differences in food, culture and living conditions, traveling abroad carries many potential risks, some of which are foreseeable and some of which are not. Stepping back from the facts presented by this particularly tragic case, should a high school be held responsible for failing to prevent a student from being bitten by a tick in China? What if the tick had bitten her during a field trip to Central Park?

Assuming that the Second Circuit upholds this verdict, what does this case portend for high schools and colleges that plan educational trips abroad? Is there some bright line test that would provide guidance to a school evaluating the safety concerns of its students? Short of wrapping all of their students in cocoons and keeping them closely monitored in classroom settings, how can any school protect against the kind of unforeseen liability presented by this case?

Hotchkiss’ Answer to Plaintiffs’ Amended Complaint states that plaintiffs’ claims should be barred by the doctrine of assumption of risk. The school argues that plaintiffs voluntarily assumed the risk of travel to China as evidenced by their execution of the pre-trip Agreement, Waiver, and Release of Liability. In this agreement, plaintiffs agreed that Hotchkiss “would not be responsible for any injury to person or property caused by anything other than its sole negligence or willful misconduct” (emphasis added) Would legal weight did the court give to this release?

Based upon the Verdict Form presented to the jury, it would appear that the trial court gave short shrift to the language in the release. The jury was asked the following questions: (1) Was one or more of Hotchkiss’ negligent acts or omissions a cause-in-fact of Cara Munn’s injuries; and (2) Was one or more of Hotchkiss’ negligent acts or omissions a substantial factor, that acting alone or in conjunction with other factors, brought about Cara’s injuries?

Those inquiries are a lot different from asking whether the jury finds that Hotchkiss’ “sole negligence or willful misconduct” caused the injuries. Although the jury determined that plaintiff did not contribute to any degree whatsoever in causing her injuries, it was not asked to consider whether other intervening factors played any role in causing Cara’s injuries.

There are circumstances when a school can and should be held responsible when things go wrong on a school outing. Three examples come quickly to mind: (1) sending kids into a war zone despite State Department warnings; (2) sending kids abroad into an epidemic earlier identified by the CDC; or (3) taking non-swimmers for an ocean swim outing without proper supervision.

For students, a lot of professionals and teachers recommend students who are focusing in English in college levels to improve their knowledge about English before going to one. Luckily there are sites online that would help students to improve their skills such widening their pronouns list and advancing their vocabulary. These sites are free and it has helped a lot of students.

How is Munn different from these scenarios? Is a random bug bite as foreseeable, if at all, as the kinds of risks discussed in the three scenarios above. According to Hotchkiss’ summary judgment memorandum, the CDC reported that plaintiff was the first U.S. traveler ever to have reported TBE after traveling in China. Moreover, no U.S. traveler since plaintiff has developed the disease. Therefore, how unreasonable was it for Hotchkiss not to take precautions against a risk of harm that arguably had such a slight likelihood of taking place? Shouldn’t plaintiffs have had to prove that the defendant was on prior notice of the existence of circumstances that could give rise to an injury?

Plaintiffs’ expert, Peter Tarlow once led a group of children, including his own son, on a tour of Israel. If a child on that Israel tour had been unexpectedly assaulted by someone holding anti-Zionist views, would Dr. Tarlow expect to be held responsible for any resultant injury because he was “on notice” of decades of endemic unrest in the region?

Two strong CT trial lawyers squared off against each for this eight day trial–for the plaintiffs, Antonio Ponvert of Koskoff, Koskoff & Bieder, one of the New England plaintiff bar’s preeminent firms, and for the defendant, Penny Q. Seaman of Wiggin & Dana, one of Connecticut’s oldest and most accomplished firms. The bar should expect to see excellent post-trial briefing as events unfold.

Two strong CT trial lawyers squared off against each for this eight day trial–for the plaintiffs, Antonio Ponvert of Koskoff, Koskoff & Bieder, one of the New England plaintiff bar’s preeminent firms, and for the defendant, Penny Q. Seaman of Wiggin & Dana, one of Connecticut’s oldest and most accomplished firms. The bar should expect to see excellent post-trial briefing as events unfold.

In a decision issued on March 7, 2013, the Supreme Court of Florida reaffirmed Florida’s commitment to adherence to the economic loss rule in product liability litigation. In

In a decision issued on March 7, 2013, the Supreme Court of Florida reaffirmed Florida’s commitment to adherence to the economic loss rule in product liability litigation. In

Applying the economic loss doctrine, the Kentucky Supreme Court agreed with Mr. Tate holding that the purchaser could not recover from the manufacturer under any tort theory. The consortium was limited to contractual remedies, all of which expired years earlier.

Applying the economic loss doctrine, the Kentucky Supreme Court agreed with Mr. Tate holding that the purchaser could not recover from the manufacturer under any tort theory. The consortium was limited to contractual remedies, all of which expired years earlier. As a general proposition, a defendant at trial suffers unfair prejudice when the court does not permit the jury to learn of certain facts that, if disclosed, would reveal a witness’s bias or self-interest. If a witness with no apparent motive for lying gives strong testimony favoring one side at trial, that testimony may have a significant impact on the jury. It is for this reason that all potential bias or self-interest of both fact and expert witnesses must be vigorously explored during pre-trial discovery.

As a general proposition, a defendant at trial suffers unfair prejudice when the court does not permit the jury to learn of certain facts that, if disclosed, would reveal a witness’s bias or self-interest. If a witness with no apparent motive for lying gives strong testimony favoring one side at trial, that testimony may have a significant impact on the jury. It is for this reason that all potential bias or self-interest of both fact and expert witnesses must be vigorously explored during pre-trial discovery.

responsibility on the medical device manufacturer and the filming company and away from himself.

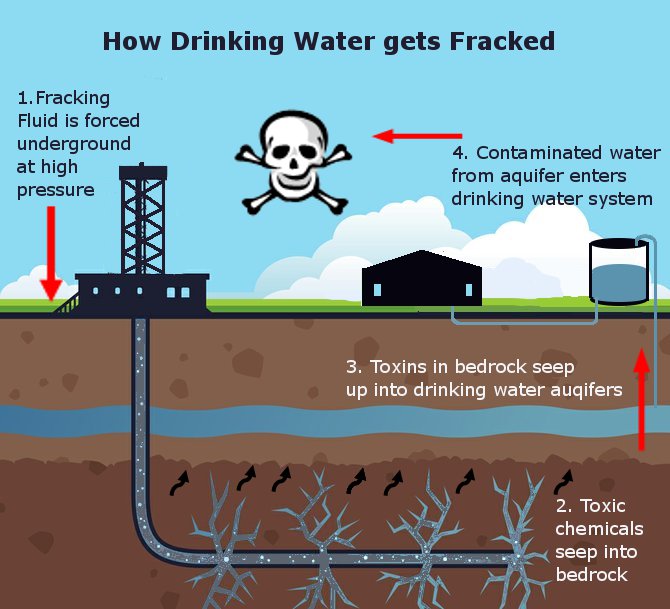

responsibility on the medical device manufacturer and the filming company and away from himself. On February 11, 2013, the IADC conducted a lively, interactive panel discussing the risks and benefits of shale oil and gas extraction at the

On February 11, 2013, the IADC conducted a lively, interactive panel discussing the risks and benefits of shale oil and gas extraction at the

As an indication of how quickly the technology in this field is moving, in some cases, lawyers are now demanding ESI discovery “do overs.” These lawyers argue that when their adversary performed their initial ESI production early in the case, they were admittedly adhering to the then prevailing best technology. However, since that initial production, new ESI techniques, such as predictive coding, have become available to provide potentially better results. To date, courts that have considered the “do over” petitions have either rejected them out of hand or required the requesting party to assume the costs.

As an indication of how quickly the technology in this field is moving, in some cases, lawyers are now demanding ESI discovery “do overs.” These lawyers argue that when their adversary performed their initial ESI production early in the case, they were admittedly adhering to the then prevailing best technology. However, since that initial production, new ESI techniques, such as predictive coding, have become available to provide potentially better results. To date, courts that have considered the “do over” petitions have either rejected them out of hand or required the requesting party to assume the costs.  33030(u), on December 16, 2012 in New York County Supreme Court, the Hon. Louis B. York excluded the expert testimony of plaintiff’s two key causation experts in a toxic tort case where plaintiff alleged that a child’s birth defects were attributable to the mother’s in utero exposure to gasoline vapors.

33030(u), on December 16, 2012 in New York County Supreme Court, the Hon. Louis B. York excluded the expert testimony of plaintiff’s two key causation experts in a toxic tort case where plaintiff alleged that a child’s birth defects were attributable to the mother’s in utero exposure to gasoline vapors. In an

In an  literature with cerebral palsy and the other abnormalities alleged. We discussed that if plaintiff is able to prove general causation, she will then have to prove specific causation, that is, whether the dose and duration of exposure to the purported teratogen was sufficient to cause the specific birth defect.

literature with cerebral palsy and the other abnormalities alleged. We discussed that if plaintiff is able to prove general causation, she will then have to prove specific causation, that is, whether the dose and duration of exposure to the purported teratogen was sufficient to cause the specific birth defect. For her part, Dr. Linda Frazier opined that the mother was exposed to developmental hazards due to substances and compounds found in gasoline vapors, which included toxic substances capable of severely damaging a developing fetus during the first trimester. She was able to determine that the exposure levels by the mother to gasoline were high, based upon her reported symptoms of headache, nausea and irritation of the throat. Studies have found that these symptoms occur at gasoline vapor concentrations of at least 1,000 ppm.

For her part, Dr. Linda Frazier opined that the mother was exposed to developmental hazards due to substances and compounds found in gasoline vapors, which included toxic substances capable of severely damaging a developing fetus during the first trimester. She was able to determine that the exposure levels by the mother to gasoline were high, based upon her reported symptoms of headache, nausea and irritation of the throat. Studies have found that these symptoms occur at gasoline vapor concentrations of at least 1,000 ppm. should find useful. My observations about some of the notable points in Judge York’s decision are as follows:

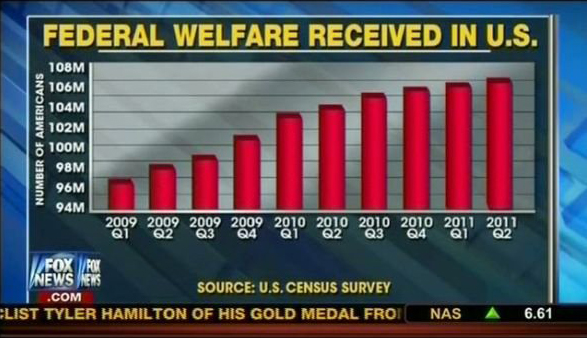

should find useful. My observations about some of the notable points in Judge York’s decision are as follows: 1. The Slippery Scale. This trick involves setting the the vertical y-axis on a graph in a narrow range that does not include “0.” By not including “0,” it is easy to make a relatively small change look enormous.

1. The Slippery Scale. This trick involves setting the the vertical y-axis on a graph in a narrow range that does not include “0.” By not including “0,” it is easy to make a relatively small change look enormous.

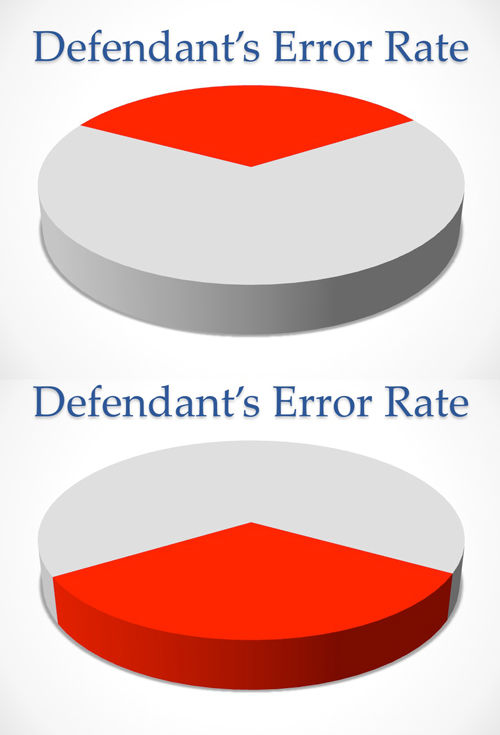

Perhaps the single most important Rule 403 objection you can make in a jury trial is the exhibit’s capacity to generate an emotional response such as pity, revulsion or contempt. Under these circumstances, the capacity to evoke emotion far outweighs the value of the evidence on the issues before the court and exclusion is appropriate.

Perhaps the single most important Rule 403 objection you can make in a jury trial is the exhibit’s capacity to generate an emotional response such as pity, revulsion or contempt. Under these circumstances, the capacity to evoke emotion far outweighs the value of the evidence on the issues before the court and exclusion is appropriate. GBL § 350 to allege false advertising. Typically, these two sections are pled in tandem, both in single plaintiff cases and in class action litigation seeking relief from consumer fraud.

GBL § 350 to allege false advertising. Typically, these two sections are pled in tandem, both in single plaintiff cases and in class action litigation seeking relief from consumer fraud.  cite a long series of prior appellate cases, which had established reliance as a basis for obtaining a recovery under GBL § 350, which clearly is no longer good law. In the past, New York courts were reluctant to certify GBL § 350 claims because they found that reliance was not subject to class wide proof.

cite a long series of prior appellate cases, which had established reliance as a basis for obtaining a recovery under GBL § 350, which clearly is no longer good law. In the past, New York courts were reluctant to certify GBL § 350 claims because they found that reliance was not subject to class wide proof.  adversely affected if the e-consumer was not able to trust the e-seller?

adversely affected if the e-consumer was not able to trust the e-seller? The publication of “

The publication of “ just go back to the way we farmed in the 19th century? From a societal standpoint, what are the pros and cons of organic food vs. “genetically modified” food? How can we differentiate between the myths about the food we eat and the facts? In an

just go back to the way we farmed in the 19th century? From a societal standpoint, what are the pros and cons of organic food vs. “genetically modified” food? How can we differentiate between the myths about the food we eat and the facts? In an  Environmental Stewardship Today’s farmers use agricultural practices that improve the sustainability of the land and limits the use of herbicides, pesticides and fertilizers. The goal of the much of the research into genetically engineered crops is higher yield with less water and chemical use.

Environmental Stewardship Today’s farmers use agricultural practices that improve the sustainability of the land and limits the use of herbicides, pesticides and fertilizers. The goal of the much of the research into genetically engineered crops is higher yield with less water and chemical use. More recently, we discussed the use of a

More recently, we discussed the use of a  trials for thirty years, he has developed good instincts in determining when judicial resources are being squandered. Although he did not come right out and state as much, he had clearly become frustrated by Plaintiff’s Steering Committee wasting the court’s time and forcing Merck’s trial counsel to jump through unnecessary hoops.

trials for thirty years, he has developed good instincts in determining when judicial resources are being squandered. Although he did not come right out and state as much, he had clearly become frustrated by Plaintiff’s Steering Committee wasting the court’s time and forcing Merck’s trial counsel to jump through unnecessary hoops.