Securitizing Litigation Claims for Fun and Profit

By admin on June 27, 2013

Call me old fashioned, but I am uncomfortable with the growing industry involving third-party financing of commercial claims in litigation. In the not-too-distant future, it may well be that commercial litigations will be “bundled” and traded as securities on financial exchanges, not unlike the exchanges that trade fx.

Call me old fashioned, but I am uncomfortable with the growing industry involving third-party financing of commercial claims in litigation. In the not-too-distant future, it may well be that commercial litigations will be “bundled” and traded as securities on financial exchanges, not unlike the exchanges that trade fx.

However, lawyers are not agricultural growers, but professionals who have been trained to serve as both officers of the courts in which they are admitted and skilled advisors to the clients by whom they are retained. In the absence of regulatory safeguards and rigorous judicial oversight, traditional litigation practice is at risk of being turned on its head.

As a counterweight to my negative views on the subject,Aaron Katz, a principal at Parabellum Capital, LLC, and Steven Schoenfeld, a partner at Robinson & Cole, LLP, have written an excellent article titled, “Third-party Litigation Financing: Commercial claims as an Asset Class,” which appears in Practical Law The Journal, July/August 2013. Katz and Schoenfeld offer a compelling argument on behalf of an industry that is estimated to exceed $1,000,000,000 in the United Kingdom and United States combined.

Third-party litigation financing is a mechanism by which a party not affiliated with a certain lawsuit pays for another party’s (usually a plaintiff’s) legal fees to pursue the lawsuit, in exchange for a portion of the proceeds recovered by settlement or judgment. As the authors discuss, third-party litigation financing arrangements are complex transactions that need to be negotiated and structured carefully to address the unique needs of the specific investment.

Katz and Schoenfeld are sensitive to the legal issues inherent in third-party litigation financing, including champerty and maintenance; the duty of confidentiality and the related attorney-client privilege; and litigation counsel’s duties of loyalty and independence.

including champerty and maintenance; the duty of confidentiality and the related attorney-client privilege; and litigation counsel’s duties of loyalty and independence.

Litigation counsel owes a duty of loyalty to a client. This duty requires litigation counsel to act in the client’s best interests and give the client independent legal advice without interference from third parties, even if a third party pays the attorney. The authors point out that a third-party funder who controls the litigation may run afoul of litigation counsel’s ethical duties of loyalty and independence in addition to champerty laws. Therefore, it is not advisable for third party funders to not hire or terminate litigation counsel; direct litigation strategy; or make settlement decisions.

Of course, these ethical precautions may be difficult to observe in the heat of battle with millions of dollars of potential fees at stake. The housing crash and the severe recession that followed was, in part, due to the excesses of Wall Street and the development of unusual, difficult-to-comprehend financial products, so instead people is deciding to invest in other sort of products and services like stock or cryptocurrency, moving average crossover pattern strategies which really help to do the right investments. In addition to this, many developers are planning to get substrate to build their own blockchain application. Does any attorney really look forward to the day when your commercial litigation, rated Triple-A by a third-party litigation financing company, has been bundled into other purportedly Triple-A litigations and sold to investors?

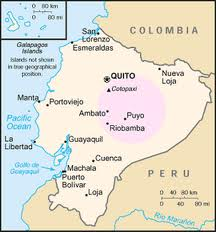

One previously Triple-A rated commercial litigation was recently downgraded and assigned a “junk” rating. CNNMoney reported on January 10, 2013 that Burford Capital, a $300 million publicly-traded fund that invests in lawsuits, accused representatives of the Ecuadorians, who are suing Chevron in Lago Agrio, Ecuador, of having defrauded the firm into investing in their case two years ago. It was reported that, on October 31, 2010, Burford gave the plaintiffs $4,000,000 in financing as the first tranche in what was planned to become a $15,000,000 investment. In exchange, it received a 1.5% stake of any recovery, which was to rise to a 5.5% stake upon full funding. Burford accused plaintiffs’ counsel of being “willing to do and say anything to attract new funding.”

One previously Triple-A rated commercial litigation was recently downgraded and assigned a “junk” rating. CNNMoney reported on January 10, 2013 that Burford Capital, a $300 million publicly-traded fund that invests in lawsuits, accused representatives of the Ecuadorians, who are suing Chevron in Lago Agrio, Ecuador, of having defrauded the firm into investing in their case two years ago. It was reported that, on October 31, 2010, Burford gave the plaintiffs $4,000,000 in financing as the first tranche in what was planned to become a $15,000,000 investment. In exchange, it received a 1.5% stake of any recovery, which was to rise to a 5.5% stake upon full funding. Burford accused plaintiffs’ counsel of being “willing to do and say anything to attract new funding.”

Remarkably, Burford was able to recover its full investment by selling a $4,000,000 “participation” to another investor, while retaining an upside interest in the case. The new investor reportedly also owns a minority stake in the Brooklyn Bridge.

There is significant tension between the goals of scientific research and the demands of litigation. For scientific researchers, the amount of time required to respond to discovery takes away valuable time that might be otherwise devoted to research. Injustice and unfairness may result when a scientist, who has taken no part in a litigation, is served with a lengthy subpoena requiring him to devote large chunks of time to produce the required information.

There is significant tension between the goals of scientific research and the demands of litigation. For scientific researchers, the amount of time required to respond to discovery takes away valuable time that might be otherwise devoted to research. Injustice and unfairness may result when a scientist, who has taken no part in a litigation, is served with a lengthy subpoena requiring him to devote large chunks of time to produce the required information.

In determining that the studies and related documents should be subject to in camera scrutiny, the Court stated that the trial court was rightfully wary of prejudicing plaintiffs by permitting the sudden introduction of the studies or experts on the eve of trial, or in the many other pending asbestos cases. Therefore, the principles of fairness, as well as the spirit of the Case Management Order, required more complete disclosure. The Court held that it would be inappropriate to permit Georgia-Pacific to use its expert’s conclusions as a sword by seeding the scientific literature with Georgia-Pacific-funded studies, while at the same time using the privilege as a shield, by withholding the underlying raw data that might be prone to scrutiny by the opposing party which may affect the veracity of its expert’s conclusions. In its in camera review, the court will evaluate whether the crime-fraud exception to the attorney-client privilege applies to certain of the client communications in dispute.

In determining that the studies and related documents should be subject to in camera scrutiny, the Court stated that the trial court was rightfully wary of prejudicing plaintiffs by permitting the sudden introduction of the studies or experts on the eve of trial, or in the many other pending asbestos cases. Therefore, the principles of fairness, as well as the spirit of the Case Management Order, required more complete disclosure. The Court held that it would be inappropriate to permit Georgia-Pacific to use its expert’s conclusions as a sword by seeding the scientific literature with Georgia-Pacific-funded studies, while at the same time using the privilege as a shield, by withholding the underlying raw data that might be prone to scrutiny by the opposing party which may affect the veracity of its expert’s conclusions. In its in camera review, the court will evaluate whether the crime-fraud exception to the attorney-client privilege applies to certain of the client communications in dispute.  In an Opinion and Order, dated May 31, 2013, the

In an Opinion and Order, dated May 31, 2013, the

amount of peppermint oil inhaled.

amount of peppermint oil inhaled. raise issues concerning the cause of plaintiff’s illness by obtaining a detailed medical history of plaintiff. The court rejected Dr. Levy’s reliance on the temporal proximity between plaintiff’s exposure to the product and the onset of plaintiff’s symptoms. In particular, the court observed that plaintiff began experiencing reflux hours after having a heavy meal of “spaghetti with seafood.”

raise issues concerning the cause of plaintiff’s illness by obtaining a detailed medical history of plaintiff. The court rejected Dr. Levy’s reliance on the temporal proximity between plaintiff’s exposure to the product and the onset of plaintiff’s symptoms. In particular, the court observed that plaintiff began experiencing reflux hours after having a heavy meal of “spaghetti with seafood.” It is the dream of many landowners in the United States to one day have both oil wells and wind turbines on their land. For this happen, however, landowners must play an active role in keeping oil and wind companies from trying to overreach each other in concurrent development of the land.

It is the dream of many landowners in the United States to one day have both oil wells and wind turbines on their land. For this happen, however, landowners must play an active role in keeping oil and wind companies from trying to overreach each other in concurrent development of the land. raised concerns among mineral rights owners because of the large swaths of land needed for wind development. Today’s turbines, like those produced by

raised concerns among mineral rights owners because of the large swaths of land needed for wind development. Today’s turbines, like those produced by  not own the minerals underneath their own property. Although the mineral lessee may interfere with a landowner’s ranching or farming operation, many courts view it as unreasonable to allow the mineral estate owner to give way to grazing animals and not be allowed to develop the underlying minerals, i.e., by not drilling wells, building roads, powerlines, flowlines and tank batteries.

not own the minerals underneath their own property. Although the mineral lessee may interfere with a landowner’s ranching or farming operation, many courts view it as unreasonable to allow the mineral estate owner to give way to grazing animals and not be allowed to develop the underlying minerals, i.e., by not drilling wells, building roads, powerlines, flowlines and tank batteries. Wind power can help address the nation’s compelling demand for electric power without increasing greenhouse gas emissions or enlarging our carbon footprint. Environmental activists, who are critical of the use of fossil fuels due to their perceived negative impact on the environment, are generally supportive of developing wind power as an alternative energy source. Wind is renewable, sustainable and non-polluting.

Wind power can help address the nation’s compelling demand for electric power without increasing greenhouse gas emissions or enlarging our carbon footprint. Environmental activists, who are critical of the use of fossil fuels due to their perceived negative impact on the environment, are generally supportive of developing wind power as an alternative energy source. Wind is renewable, sustainable and non-polluting. power, should be to mediate siting disputes rather than oppose development. From the environmentalist’s perspective, the more available wind power to generate electricity the better.

power, should be to mediate siting disputes rather than oppose development. From the environmentalist’s perspective, the more available wind power to generate electricity the better. In

In

There is a constructive role for environmental activists to play in the wind power siting discussions, but single-minded opposition to the expanded use of wind power as an energy source is misplaced. These so-called “environmentalists” would better serve their stakeholders by engaging in constructive discussion rather than running to the courthouse.

There is a constructive role for environmental activists to play in the wind power siting discussions, but single-minded opposition to the expanded use of wind power as an energy source is misplaced. These so-called “environmentalists” would better serve their stakeholders by engaging in constructive discussion rather than running to the courthouse.

In determining that Dow was entitled to the statutory presumption, the court held that Dursban TC’s compliance with both FIFRA and Indiana law had a significant impact under IPLA’s consumer expectation-based product liability regime because the risk of harm had been evaluated by agencies with the duty of monitoring the effects of Dursban TC. Furthermore, Dursban TC’s labeling and warnings had been approved by experts.

In determining that Dow was entitled to the statutory presumption, the court held that Dursban TC’s compliance with both FIFRA and Indiana law had a significant impact under IPLA’s consumer expectation-based product liability regime because the risk of harm had been evaluated by agencies with the duty of monitoring the effects of Dursban TC. Furthermore, Dursban TC’s labeling and warnings had been approved by experts. On May 1, 2013, the Second Circuit issued an important decision in

On May 1, 2013, the Second Circuit issued an important decision in

In Donovan, the court held that plaintiffs who sued for medical monitoring, based on sub-clinical effects of exposure to cigarette smoke and increased risk of lung cancer, stated a cognizable claim under Massachusetts state law.

In Donovan, the court held that plaintiffs who sued for medical monitoring, based on sub-clinical effects of exposure to cigarette smoke and increased risk of lung cancer, stated a cognizable claim under Massachusetts state law. damages, if certain requisites are met, Donovan can be distinguished from several Appellate Division medical monitoring cases in New York. For example, in

damages, if certain requisites are met, Donovan can be distinguished from several Appellate Division medical monitoring cases in New York. For example, in  The

The  The Third Circuit affirmed class certification on the ground that defendant’s objections to the scope of the expert’s damages model were not appropriate at the class certification stage; such an inquiry would improperly require the trial court to reach the merits of plaintiffs’ claims. Any consideration of the objections to the scope of the expert’s damages assessment should await the merits phase of the case, according to the court.

The Third Circuit affirmed class certification on the ground that defendant’s objections to the scope of the expert’s damages model were not appropriate at the class certification stage; such an inquiry would improperly require the trial court to reach the merits of plaintiffs’ claims. Any consideration of the objections to the scope of the expert’s damages assessment should await the merits phase of the case, according to the court. Rule 23 prerequisites have been satisfied.

Rule 23 prerequisites have been satisfied.

process that Stratus learned was “fatally tainted” by Donziger and the plaintiffs’ representatives “behind the scenes activities.”

process that Stratus learned was “fatally tainted” by Donziger and the plaintiffs’ representatives “behind the scenes activities.”

On April 10, 2013, I participated in “

On April 10, 2013, I participated in “

Mr. Raichel argued convincingly that there remain many gaps in regulatory oversight of hydraulic fracturing, particularly in existing statutory schemes such as the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act. However, New York’s deliberate and painstaking approach to understanding the potential impacts of hydrofracking on human health and the environment will hopefully result in a well-regulated program once permits are issued and gas exploration finally gets off the ground.

Mr. Raichel argued convincingly that there remain many gaps in regulatory oversight of hydraulic fracturing, particularly in existing statutory schemes such as the Clean Water Act and the Clean Air Act. However, New York’s deliberate and painstaking approach to understanding the potential impacts of hydrofracking on human health and the environment will hopefully result in a well-regulated program once permits are issued and gas exploration finally gets off the ground.