Does the Lone Pine Still Stand?

By admin on August 28, 2013

Ruling on an issue of first impression, the Colorado Court of Appeals, Division I, ruled on July 3, 2013 in Strudley v. Antero Resources Corp. that Lone Pine Orders are prohibited under Colorado law. In so holding, the court reversed the ruling of the trial court that entered a Lone Pine Order requiring plaintiffs to present prima facie evidence to support their claim that hydrofracking had contaminated their groundwater or risk having their case dismissed.

Ruling on an issue of first impression, the Colorado Court of Appeals, Division I, ruled on July 3, 2013 in Strudley v. Antero Resources Corp. that Lone Pine Orders are prohibited under Colorado law. In so holding, the court reversed the ruling of the trial court that entered a Lone Pine Order requiring plaintiffs to present prima facie evidence to support their claim that hydrofracking had contaminated their groundwater or risk having their case dismissed.

In an earlier article on this blog titled, “Lone Pine Order Ends ‘No Causation’ Hydrofracking Case,” we discussed the lower court’s rationale for dismissing plaintiffs’ case as a result of their failure to comply with the court’s Lone Pine Order requirements.

In the wake of the decision, some commentators have argued that Lone Pine Orders still remains useful in fracking litigation. Although that may be true, this observation adopts an unnecessarily narrow view of the value of Lone Pine Orders in toxic tort litigation generally. There is nothing particularly unique about hydrofracking litigation that lends itself to Lone Pine advocacy other than questionable causation, which is fairly common in toxic tort case litigation.

For example, we wrote an article on this blog concerning the Happyland Social Club Fire Litigation, which involved 87 wrongful death claims. The Bronx Supreme Court’s entry in 1992 of a Lone Pine Order was instrumental in obtaining dismissals on behalf of defendants whose products plaintiffs could not prove were present in the club at the time of the fire.

which involved 87 wrongful death claims. The Bronx Supreme Court’s entry in 1992 of a Lone Pine Order was instrumental in obtaining dismissals on behalf of defendants whose products plaintiffs could not prove were present in the club at the time of the fire.

In that case, defendants obtained a Lone Pine Order on the sole issue of product identification. Plaintiffs’ theory of the case was that the defendants’ products were fire initiators, fire promoters or, alternatively, emitted toxic fumes when burned. The contents of the social club were stored by Plaintiffs Steering Committee in a vast warehouse in Lower Manhattan. The Catch-22 for plaintiffs was that if a product was in the warehouse more or less intact, it could not have burned and contributed to the deaths of the plaintiffs. On the other hand, if the product was consumed in the fire, there was no way of identifying the product or its manufacturer. As a result, plaintiffs were not able to make a proper product identification in many instances pursuant to the Lone Pine Order and, consequently, many defendants were dismissed from the case.

Unlike the trial court in Strudley, the Happyland Lone Pine Order did not deal with the issue of medical causation, but merely product identification. To make the Lone Pine Order palatable to Plaintiffs Steering Committee, the defendants agreed to submit to limited deposition and document discovery solely on the issue of product identification. In doing so, the defendants avoided having to take discovery in 87 wrongful death cases, most of which would have been conducted in Ecuador.

Unlike the trial court in Strudley, the Happyland Lone Pine Order did not deal with the issue of medical causation, but merely product identification. To make the Lone Pine Order palatable to Plaintiffs Steering Committee, the defendants agreed to submit to limited deposition and document discovery solely on the issue of product identification. In doing so, the defendants avoided having to take discovery in 87 wrongful death cases, most of which would have been conducted in Ecuador.

If the Lone Pine Order entered by the trial court in Strudley had a weakness, it was perhaps that the order imposed too long a laundry list of demands for plaintiffs to meet. Perhaps the defendants were too successful in having the trial court adopt their argument. In the final analysis, however, it may have made no difference how the Lone Pine Order was structured if the Lone Pine concept is not recognized under Colorado jurisprudence.

In my experience, the simpler the Lone Pine Order, the better. After years of litigation, an Oklahoma state court judge, Deborah C. Shallworth, entered a Lone Pine Order in the Page Belcher Federal Building PCB Litigation, which was a toxic tort litigation against Public Service of Oklahoma, arising from an alleged PCB exposure in the aftermath of a transformer fire. Pursuant to that Lone Pine Order, plaintiffs were required to submit affidavits from their medical doctors establishing a causal link between the injury alleged and PCB exposure. Although a seemingly simple requirement (as compared to what was demanded of plaintiffs in Strudley), many of the Oklahoma plaintiffs could not meet the requirement and their cases were dismissed.

The Colorado Court of Appeals decision in Strudley should be studied by toxic tort practitioners interested in Lone Pine jurisprudence. The opinion contains an excellent survey of Lone Pine orders adopted in other jurisdictions. At the same time, the decision cites those cases in which courts have expressed concern about their “untethered use.” Thus, practitioners on both sides of the toxic tort bar can find helpful language in the opinion.

Are there other uses of Lone Pine Orders other than providing better case management? In an article published in Law 360 titled, “Lone Pine Orders Are Still Useful in Fracking Litigation,” (August 7, 2013), Michael K. Murphy of Gibson Dunn & Crutcher LLP, argues that a Lone Pine Order forces a plaintiff to pick a theory and live with it, providing defendants with a target for later discovery and expert attacks. Therefore, Murphy contends that, even though the entry of a Lone Pine Order does not result in dismissal of plaintiff’s case, it may provide a tactical advantage to defendants later on. In particular, he points to Baker, et al. v. Anschutz Exploration Corp., No. 11-06119 (W.D.N.Y.) (Doc. 112, filed June 27, 2013), as an illustration of this strategy. By coincidence, the same plaintiff law firm represented the plaintiffs in both Baker and Strudley.

On a motion for spoliation sanctions, it makes no difference that a party destroyed emails without “malevolent” purpose. For a sanctions motion to be granted, it is necessary only to demonstrate that the evidence was destroyed deliberately.

On a motion for spoliation sanctions, it makes no difference that a party destroyed emails without “malevolent” purpose. For a sanctions motion to be granted, it is necessary only to demonstrate that the evidence was destroyed deliberately. It emerged during discovery that Sekisui had not placed a

It emerged during discovery that Sekisui had not placed a  possible. However, it is not enough to have the client merely distributing the litigation hold to the staff. It is necessary to ensure that the correct individuals are sent the notice and that they completely understand their legal obligations with regard to ESI preservation. Following up with the client on preservation compliance after the litigation hold is sent is essential in avoiding potentially catastrophic result.

possible. However, it is not enough to have the client merely distributing the litigation hold to the staff. It is necessary to ensure that the correct individuals are sent the notice and that they completely understand their legal obligations with regard to ESI preservation. Following up with the client on preservation compliance after the litigation hold is sent is essential in avoiding potentially catastrophic result. When the preemption defense is not available, it may still be possible to effectively dismiss a plaintiff’s claim by arguing that the court should consider primary jurisdiction. Primary jurisdiction is a judicially created doctrine that addresses the proper relationship between court and administrative agencies.

When the preemption defense is not available, it may still be possible to effectively dismiss a plaintiff’s claim by arguing that the court should consider primary jurisdiction. Primary jurisdiction is a judicially created doctrine that addresses the proper relationship between court and administrative agencies.

The NYLCV’s

The NYLCV’s  fighting for our future until we are start drilling here in New York state”. In an

fighting for our future until we are start drilling here in New York state”. In an  Local bans on hydraulic fracturing continue to be fiercely debated as the use of hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas development of shale reserves increasingly gains in popularity. Grassroots opponents of hydraulic fracturing increasingly stress the non-environmental social impacts that have become associated with hydraulic fracturing in certain rural communities.

Local bans on hydraulic fracturing continue to be fiercely debated as the use of hydraulic fracturing for oil and gas development of shale reserves increasingly gains in popularity. Grassroots opponents of hydraulic fracturing increasingly stress the non-environmental social impacts that have become associated with hydraulic fracturing in certain rural communities.  their communities.

their communities. Pennsylvanians now await a decision from the Supreme Court, in the wake of a Commonwealth Court decision, which found that that Act 13 cannot restrict zoning. The state had argued in that case that zoning provisions in Act 13 do not pre-empt local governments from enacting zoning ordinances so long as they did not place any restrictions on the location of oil and gas drilling operations in conflict with Act 13.

Pennsylvanians now await a decision from the Supreme Court, in the wake of a Commonwealth Court decision, which found that that Act 13 cannot restrict zoning. The state had argued in that case that zoning provisions in Act 13 do not pre-empt local governments from enacting zoning ordinances so long as they did not place any restrictions on the location of oil and gas drilling operations in conflict with Act 13.  Rule 30(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides an efficient means of identifying the corporate representative with the most relevant knowledge concerning particular subjects at issue in a case. When a requesting party cannot identify the appropriate corporate witness to testify about particular activities or documents, Rule 30(b)(6) can be an invaluable tool.

Rule 30(b)(6) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure provides an efficient means of identifying the corporate representative with the most relevant knowledge concerning particular subjects at issue in a case. When a requesting party cannot identify the appropriate corporate witness to testify about particular activities or documents, Rule 30(b)(6) can be an invaluable tool. notice. Is the notice overly broad and burdensome? Is the notice so vague that it is unclear precisely what information will be elicited at the deposition? Prior to discussing with the client what witness or witnesses to produce, it is imperative that both counsel and the client have a clear idea concerning the scope of the notice. The failure to timely object to the notice may come back to haunt the unwary defense counsel.

notice. Is the notice overly broad and burdensome? Is the notice so vague that it is unclear precisely what information will be elicited at the deposition? Prior to discussing with the client what witness or witnesses to produce, it is imperative that both counsel and the client have a clear idea concerning the scope of the notice. The failure to timely object to the notice may come back to haunt the unwary defense counsel. Of course, all answers are on behalf of the corporation and have the potential to be used against it , regardless of how the witness attempts to qualify an answer.

Of course, all answers are on behalf of the corporation and have the potential to be used against it , regardless of how the witness attempts to qualify an answer.  Federal court practitioners are well-advised to be aware of the key provisions of the

Federal court practitioners are well-advised to be aware of the key provisions of the

amount in controversy by a “preponderance of the evidence.” Under the new rule, if challenged, a defendant is required to present more than a conclusory statement that the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000.

amount in controversy by a “preponderance of the evidence.” Under the new rule, if challenged, a defendant is required to present more than a conclusory statement that the amount in controversy exceeds $75,000. The typical “take-home” plaintiff is a bystander such as the child who claims she was exposed to asbestos while playing in the basement where her father’s work clothes covered with asbestos dust were laundered. Across the United States, the battle lines are being drawn in these “take-home” or “household” asbestos cases. In a

The typical “take-home” plaintiff is a bystander such as the child who claims she was exposed to asbestos while playing in the basement where her father’s work clothes covered with asbestos dust were laundered. Across the United States, the battle lines are being drawn in these “take-home” or “household” asbestos cases. In a  "limitless liability", New York trial courts continue to distinguish cases on their facts to permit recovery for "take-home" claimants.

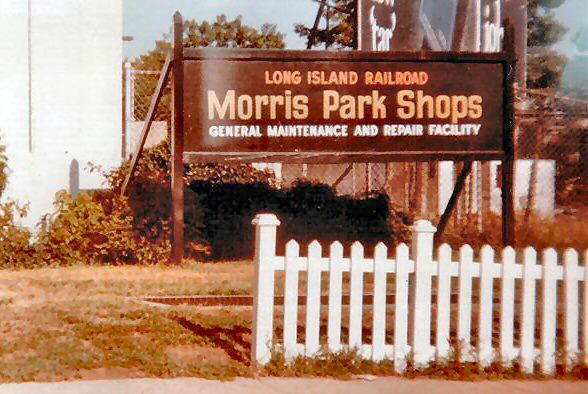

"limitless liability", New York trial courts continue to distinguish cases on their facts to permit recovery for "take-home" claimants.  Judge Heitler ruled that the Court of Appeals holding in Holdampf could not be relied upon by the LIRR because the facts presented in Frieder were different, to wit, LIRR had control of the workplace where the dinner was located (inside the walls of the rail yard). Under this unique set of facts, she reasoned, her ruling would neither run afoul of Holdampf nor open the floodgates of "limitless liability". Based upon her discussion of the "take-home" case law, Judge Heitler appears prepared to apply the brakes to "take-home" asbestos claims in New York City.

Judge Heitler ruled that the Court of Appeals holding in Holdampf could not be relied upon by the LIRR because the facts presented in Frieder were different, to wit, LIRR had control of the workplace where the dinner was located (inside the walls of the rail yard). Under this unique set of facts, she reasoned, her ruling would neither run afoul of Holdampf nor open the floodgates of "limitless liability". Based upon her discussion of the "take-home" case law, Judge Heitler appears prepared to apply the brakes to "take-home" asbestos claims in New York City.  and enjoyment of land is both “substantial and unreasonable.” Courts are cognizant that lots of people, who sometimes speak too loudly, smell badly or otherwise do not show proper regard for their neighbors, are thrown together in close proximity, particularly in urban settings, To permit these petty annoyances to be actionable as private nuisance would result in flooding our court system with trivial and nonsensical disputes.

and enjoyment of land is both “substantial and unreasonable.” Courts are cognizant that lots of people, who sometimes speak too loudly, smell badly or otherwise do not show proper regard for their neighbors, are thrown together in close proximity, particularly in urban settings, To permit these petty annoyances to be actionable as private nuisance would result in flooding our court system with trivial and nonsensical disputes.  "A Mills Brothers hit from the 1930’s asks the musical question:

"A Mills Brothers hit from the 1930’s asks the musical question:

Rather, courts examine nuisance claims brought by “sensitive” individuals, such as Schuman, by applying an objective standard, i.e. whether the smoke would cause physical discomfort and annoyance in persons of ordinary sensibilities. It is noteworthy that plaintiff’s expert,

Rather, courts examine nuisance claims brought by “sensitive” individuals, such as Schuman, by applying an objective standard, i.e. whether the smoke would cause physical discomfort and annoyance in persons of ordinary sensibilities. It is noteworthy that plaintiff’s expert,  commenced, the Coop has initiated a procedure pursuant to which coop owners along a row of units can now voluntarily revise their

commenced, the Coop has initiated a procedure pursuant to which coop owners along a row of units can now voluntarily revise their  The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in

The U.S. Supreme Court’s decision in  commentators offer the view that pesticide manufacturers may now be protected from plaintiff alleging a stop-selling theory of liability. If the case’s holding is so extended, plaintiffs should no longer be able to allege that an herbicide manufacturer should not have placed a pesticide into commerce in the first instance. In essence, this is a variation of the often espoused argument that a product should not be marketed because its risks outweigh any potential benefits. After all, the whole point of federal regulation is the underlying assumption you are going to market the product.

commentators offer the view that pesticide manufacturers may now be protected from plaintiff alleging a stop-selling theory of liability. If the case’s holding is so extended, plaintiffs should no longer be able to allege that an herbicide manufacturer should not have placed a pesticide into commerce in the first instance. In essence, this is a variation of the often espoused argument that a product should not be marketed because its risks outweigh any potential benefits. After all, the whole point of federal regulation is the underlying assumption you are going to market the product.