Does Preemption Prevent Redress For Homeowners Impacted By Polluters’ Air Emissions?

By admin on October 29, 2013

On April 23, 2012, residents of rural Muscatine, Iowa filed a class action lawsuit titled, Laurie Freeman et al. v. Grain Processing Corporation (case no. LACV 021232), in the Iowa District Court for Muscatine County. The defendant, Grain Processing Corporation, is an Iowa manufacturer of corn syrup, starches and alcohols. Plaintiffs sought compensation for property damage and adverse health effects on behalf of all putative class members (some 17,000 people) residing within three miles of the facility.

On April 23, 2012, residents of rural Muscatine, Iowa filed a class action lawsuit titled, Laurie Freeman et al. v. Grain Processing Corporation (case no. LACV 021232), in the Iowa District Court for Muscatine County. The defendant, Grain Processing Corporation, is an Iowa manufacturer of corn syrup, starches and alcohols. Plaintiffs sought compensation for property damage and adverse health effects on behalf of all putative class members (some 17,000 people) residing within three miles of the facility.

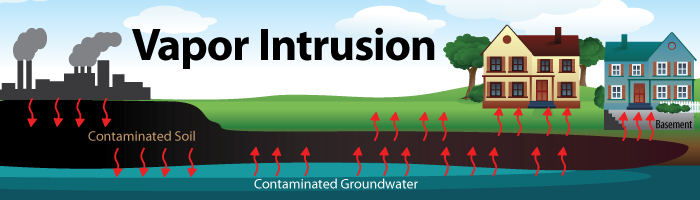

Plaintiffs alleged that Grain Processing’s industrial production caused the release of polluting chemicals and particles from the facility on to nearby homes, schools and churches. As a result, particulate matter, in the form of soot or smoke, was alleged to have been visibly left on, and in, these structures, and the yards and grounds around these structures.

Plaintiffs asserted claims pursuant to statutory and common law nuisance, trespass and negligence. Plaintiffs specifically denied that they were bringing their claims under the federal or state Clean Air Acts. Plaintiffs sought damages to remediate their properties, compensation for the loss of use and enjoyment of their properties, punitive damages and possible injunctive relief.

Plaintiffs asserted claims pursuant to statutory and common law nuisance, trespass and negligence. Plaintiffs specifically denied that they were bringing their claims under the federal or state Clean Air Acts. Plaintiffs sought damages to remediate their properties, compensation for the loss of use and enjoyment of their properties, punitive damages and possible injunctive relief.

On December 21, 2012, Grain Processing filed a motion for summary judgment centered on preemption of plaintiffs’ claims by existing federal and state regulations. On March 27, 2013, District Court Judge Mark J. Smith granted defendant’s motion and dismissed the case. The matter is now on appeal to the Iowa Supreme Court.

On summary judgment, Grain Processing argued that plaintiffs’ common law claims should be dismissed because they were preempted by the Clean Air Act and accompanying state laws. The defendant argued implied preemption by field and conflict preemption, rather than express preemption, barred plaintiffs’ claims. In large part, the trial court relied upon the United States Supreme Court’s decision in American Electric Power Co., Inc. v. Connecticut, 131 S.Ct. 2527 (2011), which held that the Clean Air Act displaced any federal common law right to seek abatement of carbon dioxide emissions from fossil fuel-fired power plants. There, the Supreme Court remarked that EPA is surely better equipped to do the job that individual district judges issuing ad hoc, case-by-case injunctions because federal judges lacked the expertise and means to make such decisions.

The Iowa trial court also heavily relied on Bell v. Cheswick Generating Station, 2:12-cv-929, 2012 WL 4857796 (W.D. Pa. Oct. 12, 2012). In that case, plaintiffs brought a class action lawsuit against a coal-fired power plant, which they claimed deposited air emissions on nearby property. The Bell court dismissed plaintiffs’ claims because “to conclude otherwise would require an imperceptible determination regarding the reasonableness of an otherwise government regulated activity.”

The summary judgment record includes plaintiffs’ allegation that Grain Processing had violated the federal Clean Air Act in all twelve of the most recent twelve quarters and had been designated by EPA as a “High Priority Violator.” Plaintiffs’ expert also determined that Grain Processing’s record of environmental compliance had been poor. During a plant inspection, the expert observed leaking valves, pumps and unions that “are sources of volatile, odorous and corrosive, fugitive emissions which exposed both workers and the community.” He reported “horrible neglect” of dryer units, “antiquated” control rooms and “a complete breakdown of environmental awareness and safety” in management operations.

Judge Smith remarked that if half of the expert findings were true, there had been a blatant disregard for both the environment and the community of Muscatine. Deficiencies had become so bad by 2012 that the Iowa Department of Natural Resources (“DNR”) commenced a civil action against the company. In 2009, a DNR inspector sent an email to an agency lawyer citing an "obvious blue haze generated by the plant and drifting over Muscatine neighborhoods."

Judge Smith grappled with the issue of whether plaintiffs’ common law action would interfere with or contravene DNR’s remedies for these very issues if plaintiffs were successful in obtaining an injunction specifying what Grain Processing must do to remedy these problems. Judge Smith granted the motion to dismiss the action, although he conceded that the action taken by the regulatory agency would not remedy the harm each individual plaintiff or class member had incurred as a result of the polluter’s actions or inactions. Nevertheless, Judge Smith feared that to do otherwise would allow the same regulatory patchwork proscribed by the U.S. Supreme Court.

On the appeal, a well-reasoned amici curiae brief has been filed on behalf of the National Association of Manufacturers, and other interested industry groups, in support of Grain Processing. The brief was submitted by Richard O. Faulk of Hollingsworth LLP and Sarah E. Crane of the Davis Brown Law Firm.

In particular, the amici emphasize the application of the “political question” doctrine, and focus in on the second test stated in Baker v. Carr, 369 U.S. 186 (1962), namely whether the courts lack “judicially discoverable and manageable standards” for resolving nuisance cases involving regulated pollutants.

Such cases, amici argue, raise quintessential “political questions” because they would require courts to make policy judgments instead of abiding by the requirement that judicial action be governed “by standard, by rule.” The amici contend that the trial court does not have the investigative resources and technical and scientific expertise necessary to create the standards and rules needed to resolve the controversy justly. According to the amici, such inquiries go to the very heart of the political question doctrine.

Such cases, amici argue, raise quintessential “political questions” because they would require courts to make policy judgments instead of abiding by the requirement that judicial action be governed “by standard, by rule.” The amici contend that the trial court does not have the investigative resources and technical and scientific expertise necessary to create the standards and rules needed to resolve the controversy justly. According to the amici, such inquiries go to the very heart of the political question doctrine.

The appeal raises important questions that will no doubt be challenging for the Iowa Supreme Court to resolve. On the one hand, the court will not want to permit the plaintiffs to supplant the role or the authority of the DNR. On the other hand, the court will be under pressure to provide some form of redress for Muscatine residents that have suffered nuisance and property damage as a result of the alleged environmental violations of their industrial neighbor.

Ideally, Grain Processing should provide homeowners in Muscatine a Value Assurance Plan to protect homeowners’ investment in their homes. If, as Grain Processing contends, a proposed upgrade of plant pollution control equipment, will address air emission concerns to the satisfaction of residents, the Value Assurance Plan would likely cost Grain Processing little, but provide enormous piece of mind to the company’s neighbors.

Often the physician, a trained clinician, will testify that she was familiar with the risks in question and did not need to be provided a warning. Alternatively, the physician may testify that a stronger warning would not have influenced her decision to prescribe the drug and that she still prescribes the drug, although the problem with this, is that some drugs are known for causing addiction sometimes, so the use of an

Often the physician, a trained clinician, will testify that she was familiar with the risks in question and did not need to be provided a warning. Alternatively, the physician may testify that a stronger warning would not have influenced her decision to prescribe the drug and that she still prescribes the drug, although the problem with this, is that some drugs are known for causing addiction sometimes, so the use of an  to every warning claim – the defect (whatever is allegedly wrong with the warning) has to cause the injury. If the prescribing physician never even read the purportedly inadequate warning, none of those inadequacies could have affected his/her treatment of the patient.”

to every warning claim – the defect (whatever is allegedly wrong with the warning) has to cause the injury. If the prescribing physician never even read the purportedly inadequate warning, none of those inadequacies could have affected his/her treatment of the patient.” The traditional rule in tort law is that the threat of future harm, not yet realized, is not sufficient to state a claim. However, over the past twenty-five years, plaintiffs in toxic tort litigation have sought to assert new non-injury damage claims, such as medical monitoring and fear of cancer. Providing compensation for an event that has not yet occurred and, indeed, may never occur, is a long way from traditional tort, which only permits recovery when a victim has suffered a harm.

The traditional rule in tort law is that the threat of future harm, not yet realized, is not sufficient to state a claim. However, over the past twenty-five years, plaintiffs in toxic tort litigation have sought to assert new non-injury damage claims, such as medical monitoring and fear of cancer. Providing compensation for an event that has not yet occurred and, indeed, may never occur, is a long way from traditional tort, which only permits recovery when a victim has suffered a harm. The Veterans Administration has developed a

The Veterans Administration has developed a

As the Ninth Circuit held in

As the Ninth Circuit held in  Some environmental practitioners contend that Phase I site assessments, commonly used in real estate transactions, will now be more costly and time consuming due to the new standard. Seyfarth Shaw counsels in its

Some environmental practitioners contend that Phase I site assessments, commonly used in real estate transactions, will now be more costly and time consuming due to the new standard. Seyfarth Shaw counsels in its  indoor air samples as part of its Phase I.

indoor air samples as part of its Phase I. applying advanced neuroscientific techniques to pretrial discovery and trial.

applying advanced neuroscientific techniques to pretrial discovery and trial. the new bible of advocacy. The Seattle Zen Legal Blog authored by plaintiff lawyer

the new bible of advocacy. The Seattle Zen Legal Blog authored by plaintiff lawyer  Graham & Laney PA in Columbia, South Carolina, provides an in-depth discussion of new trial strategy in “

Graham & Laney PA in Columbia, South Carolina, provides an in-depth discussion of new trial strategy in “ make a judgment based on that virtual reality. Ball and Keene provide advice to their readers on how to circumvent this evidentiary rule. ”

make a judgment based on that virtual reality. Ball and Keene provide advice to their readers on how to circumvent this evidentiary rule. ” flashlight of attention which can refigure the brain and change behavior.”

flashlight of attention which can refigure the brain and change behavior.” Justice Manuel J. Mendez determined in

Justice Manuel J. Mendez determined in  The October 2012 incident launched stories in all of New York’s major newspapers including the Daily News, which ran an article with the headline, “

The October 2012 incident launched stories in all of New York’s major newspapers including the Daily News, which ran an article with the headline, “ close call. Taking this teacher out of the classroom was “excessive and shocking.”

close call. Taking this teacher out of the classroom was “excessive and shocking.” In January 2013,

In January 2013,  be able to produce all relevant discovery, including ESI, in litigation. What happens when the vendor is unwilling or unable to provide the client with the data required for discovery? What if the discovery vendor shuts its doors? Will the company be hit with spoliation of evidence sanctions? How would Judge Shira Scheindlin respond if presented with a motion for spoliation sanctions? The short answer is that it probably depends on the circumstances.

be able to produce all relevant discovery, including ESI, in litigation. What happens when the vendor is unwilling or unable to provide the client with the data required for discovery? What if the discovery vendor shuts its doors? Will the company be hit with spoliation of evidence sanctions? How would Judge Shira Scheindlin respond if presented with a motion for spoliation sanctions? The short answer is that it probably depends on the circumstances. As

As  A visitor to Capitol Hill might come away with the impression that there are serious questions about whether climate change is occurring and, if it is, whether it is caused by human activity. But one place where there are few such questions is the courts.

A visitor to Capitol Hill might come away with the impression that there are serious questions about whether climate change is occurring and, if it is, whether it is caused by human activity. But one place where there are few such questions is the courts.

A substantial effort has been mounted to urge the Colorado Supreme Court to reverse the intermediate appellate court’s ruling on July 3, 2013 in Strudley v. Antero Resources Corp., which determined that Lone Pine Orders are prohibited under Colorado law. In so holding, the Strudley court reversed a trial court ruling that had dismissed plaintiffs’ case for failing to provide the court with any competent prima facie evidence of causation. We discussed the appellate court holding in a recent article, "

A substantial effort has been mounted to urge the Colorado Supreme Court to reverse the intermediate appellate court’s ruling on July 3, 2013 in Strudley v. Antero Resources Corp., which determined that Lone Pine Orders are prohibited under Colorado law. In so holding, the Strudley court reversed a trial court ruling that had dismissed plaintiffs’ case for failing to provide the court with any competent prima facie evidence of causation. We discussed the appellate court holding in a recent article, " nature, entered a Lone Pine Order requiring plaintiffs to make an early prima facie showing of exposure and causation. When plaintiffs failed to meet this burden, the trial court dismissed plaintiffs’ case. A Lone Pine Order typically requires a plaintiff to present sufficient evidence prior to full discovery to establish a foundational evidentiary showing of one or more critical elements of the claims, or to risk possible dismissal.

nature, entered a Lone Pine Order requiring plaintiffs to make an early prima facie showing of exposure and causation. When plaintiffs failed to meet this burden, the trial court dismissed plaintiffs’ case. A Lone Pine Order typically requires a plaintiff to present sufficient evidence prior to full discovery to establish a foundational evidentiary showing of one or more critical elements of the claims, or to risk possible dismissal. In arguing for a case management scheme that would permit the Colorado trial courts to apply Lone Pine, CCJL cautions that Lone Pine is hardly a hammer that should be arbitrarily or routinely invoked and is not by any means a substitute for summary judgment. In summary, CCJL argues that Strudley is bad precedent that will only obstruct the creativity of trial judges in managing their cases.

In arguing for a case management scheme that would permit the Colorado trial courts to apply Lone Pine, CCJL cautions that Lone Pine is hardly a hammer that should be arbitrarily or routinely invoked and is not by any means a substitute for summary judgment. In summary, CCJL argues that Strudley is bad precedent that will only obstruct the creativity of trial judges in managing their cases.